ADILA LAÏDI-HANIEH

THE ARCHIVE OF UN-FAMILIAR STORIES

Bir Zeit, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh is an Algerian-Palestinian art historian and cultural manager. She was the Director General of the private Palestinian Museum in Birzeit from 2018 to 2023. Dr. Laïdi-Hanieh developed the Museum’s first five-year program strategy, encompassing knowledge production and research, multi-generational education, collections valorization, digital platforms, and an original historical exhibitions program. During her tenure, the museum won the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

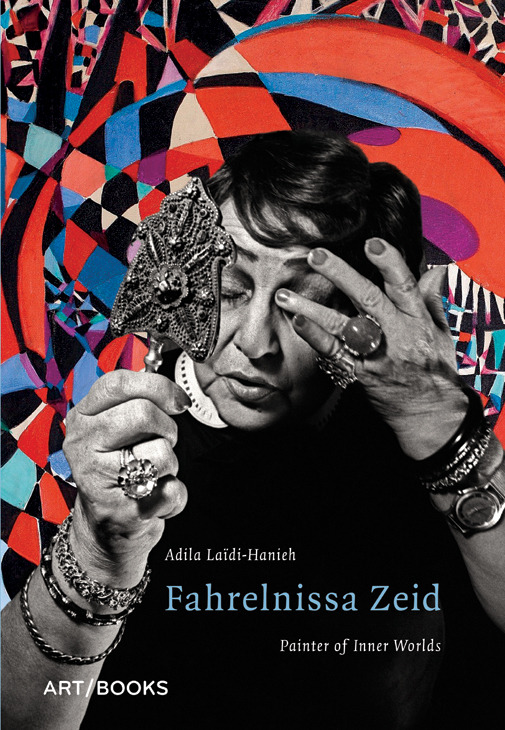

Previously, she was the founding director of the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre in Ramallah, building its programs around three foci: Cultural identity, visual arts, and outreach. Dr. Laïdi-Hanieh published several books and essays, including the biography of the Turkish modernist artist “Fahrelnissa Zeid. Painter of Inner Worlds“ (2017.) She also published the cultural anthology “Palestine. Rien ne nous manque ici,” (2009) which interrogates and celebrates contemporary Palestine. Her academic work encompasses critical theory, aesthetics, museology, and ideology theory. Dr. Laïdi-Hanieh received a PhD. in Cultural Studies from George Mason University, and obtained an MA in Arab Studies from Georgetown University. She taught at Birzeit University.

Courtesy Columbia University Global Center in Amman (CGC Amman)

ADILA, I WOULD LIKE TO HEAR YOUR PERSONAL DEFINITION OF ARCHIVE.

It’s an uncut, unedited trace of being -and of doing- in the world.

COULD YOU GIVE EXAMPLES OF YOUR WAY OF WORKING WITH ARCHIVES WITHIN YOUR OWN EXPERIENCE?

I can best speak about my direct work on the archives of Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901-1991). I also have experience running an organization working on an archive project of digitization, the Palestinian Museum. It was a large project that digitized hundreds of thousands of items of ephemera spanning 150 years of Palestinian local and diasporic social history. We had a large team with tens of highly trained historical researchers, archivists, digitizers etc. In its original active phase, it lasted six years, from 2018 to 2024. Its website is still on, open access and interactive. From its inception I contributed to the strategy and oversaw operations. In both cases— and even though the archives and their economic and political circumstances are vastly different — we are talking about absence, piecing together a presence, an action and maybe a claim and a right through the archives. It is about reconstituting a presence that may have been ignored or denied.

LET’S TALK ABOUT THE FAHRELNISSA ZEID ARCHIVE FIRST. WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY RECONSTITUTING A PRESENCE OUT OF ABSENCE?

I started to work in a room full of almost seventy years’ worth of papers and photographs. Mostly paper, unfolded sometimes and unopened, uncatalogued. So, I had to manually scope, go through everything, select what was of importance for my book, and ultimately, demonstrate that this artist had certain thoughts on her practice, and performed certain actions, that she existed at a certain point of time and her acts and actions have value. I could not have done that without her personal archive. I am grateful to the family of the artist, and especially to her daughter in law Princess Majda (1942-2025), for their generosity and trust in allowing me to delve into this family trove, and for answering questions to fill in gaps. This work was the basis to then go on and conduct interviews with contemporaries of the artist, conduct further archival research in libraries and archival funds, and undertake art historical analysis and research. The departure point was the black hole so to speak of her own archives and private papers. Of course, we knew the highlights of this artist’s life: a woman ahead of her time, who overcame adversities while leading an artistic career in two capitals in Europe, in Turkey, then in Jordan. But there were gaps. For example, where she exhibited exactly, who were her contemporaries among artists, gallerists, and critics? What she exhibited, and most importantly what the reception was. The lucky thing about Fahrelnissa is that she was self-aware and kept duplicates of everything: her exhibition catalogues, her reviews, drafts of the personal letters, drafts of answers to interviews, notes about books she read, etc. And this is only the manuscript and documentary archive, in addition to a rich trove of sketchbooks and sketches on loose leaf. I am lucky to have worked on the archive of a person who was the product of a certain nineteenth century education and culture, who were used to consign everything to the written page. Beyond the reconstruction of her career, a thread ran through my research -the archival work and the interviews: To understand whether, and how, Fahrelnissa Zeid was an artist influenced by “Byzantine” and “Islamic” arts, as she was uniformly described. I knew the artist as an adolescent, as was lucky to receive painting lessons from her for a few formative years, and I never noticed that dimension in her instruction nor in conversation. So, when I started working about Fahrelnissa in 2015, I doubted that ascribed genealogy. There were published interviews of her in the 1950s where she spoke clearly of her approach to art, but her statements were ignored in favor of the invention of a fanciful orientalist label conjured by Parisian critics in the 1950s. Just like their predecessors twenty years before had ascribed to Latin American artist primitivist esthetics and filiations. This orientalist label was then reprised and expanded by nativist and culturalist art professionals and journalists. I had an open mind and thought she may in fact have been an artist earnestly trying to marry an interest in her vernacular heritage with a contemporary visual perspective, like many modernist pioneers form the Global South. However, what is interesting when working in an archive is what it shows and what it elides. The positive traces and the absences. I did not find anything about that culturalist quest or influences. No handwritten notes, no books, no sketches. On the other hand, I did find both in the archive and in my interviews a confirmation of her singular lifelong interest in the cosmos, the cosmos as a sublimation of her subjectivity, and a spiritual communion via her artistic practice with extra-physical forces. The archive helped me make an argument about that. To answer your main question, the archives were an aid in making a case about Fahrelnissa Zeid: she was a member of certain art collectives, at certain key periods of time, in certain areas of the world. This is what she thought about her art, this is where she exhibited, this is who wrote about her, and this is what influenced her. So, this is who she was as an artist, with a full practice and unprecedented achievements, despite her absence from canonical art narratives of the cities where she led her career: Istanbul in the 1940s, London in the 1940s and 1950s, and Paris from the 1950s to the early seventies.

SO, THE ARCHIVE AS FACT-PROVIDER, FOR YOU. YOU COULD FIND ANSWERS IN THERE THAT WERE NOWHERE ELSE. WAS IT HELPFUL TO HAVE A MORE ACCURATE GLIMPSE OF THE PERSONA OF FAHRELNISSA ZEID AS WELL?

There is content and there is form. In terms of content, she wrote about her life, and she also wrote about her mood episodes, sadness, elation, fatigue, exaltation, excitement, and depression. She projected her feelings onto her diaries, her sketches, and letters. Also, you can tell from the form, the speed of the drawing, the handwriting, what mood she was in. You could read her like a seismograph. I felt that even if I did not know her as an adult, there she was, in her archive. She projected herself through the writing. On the other hand, there are things that I did not find, and that I was hoping to find. Why did she paint certain works and in a given style? Or, for example, when she would change from one abstract style to another. And then when she went back to the figurative, she did not fully document all the reasons. There are a few traces from which to start, with a few self-aware, clear, and decisive statement, but overall, those changes were manifested artistically rather than articulated intellectually.

THE ARCHIVES THAT YOU HAD ACCESS TO WERE JUST HER ARCHIVES OR OTHER SOURCES AS WELL?

There were many letters from family members living in different areas of the globe, making letter writing a necessity. But I was more interested in excavating the history of the artist and her artistic context, rather than her life. Especially given that her daughter, Shirin Devrim (1926-2011), had published a multigenerational family biography, focused on her mother: A Turkish Tapestry (1996).

HOW DO YOU THINK THAT WORKING WITH HER ARCHIVES INFORMED YOUR OWN WAYS OF UNDERSTANDING ARCHIVES AFTERWARDS?

Obviously, it made me more aware of the importance of keeping archives. Paradoxically, another element I understood is the importance of critical reading and not taking the archives or the document at face value. What is in the document is not the comprehensive reflection. You need to contextualize it, to put it in relation with something else. And we should not fetishize archives. I was lucky that her archive -both the printed matter and her manuscript letters and diaries- reflected Fahrelnissa Zeid’s character, career, and psyche. But still, I did not take it at face value and had to, for example reconstruct or understand the missing part of a correspondence, or the setting or an interview, or the history of encounters with certain people, the circumstance of an exhibition, etc.

TELL ME ABOUT THE STRATEGY THAT YOU IMPLEMENTED FOR ARCHIVES AT THE PALESTINIAN MUSEUM.

The Palestinian Museum Digital Archives predated by a few months my coming to work at the museum. There was a brief about collecting endangered items. Whether physical danger, or neglect. So, when I arrived there was already a lot of material gathered by my colleagues. Because unlike straightforward archival digitization projects, ours -given Palestinian history of dispossession and forced dispersal- had first to assemble an archive from owners who had hid it to preserve it; or conversely, to convince individuals that the material they held was in fact an archive. The next issue was selection: how to choose and not keep everything that people offered us. A social history digital archive can be initiated by a university, or a library. But since we were a museum, we had certain cultural interests, which ought to be reflected in the issues that we collected. Still, in a situation like Palestine and Palestinian archives, where very existence is denied, or is threatened with disappearance, it’s difficult to be selective. Palestinian society has always been in survival mode. Palestinian archives were stolen by Israel in 1948 and shut, and then in 1982 during the Lebanon invasion. There is a PLO archive that was preventively sent to Germany in 1982. So, you have archives which are destroyed, archives which are lost and archives which are stolen. Then, when you come to areas in the West Bank in Palestine, that have not been bombed out or completely destroyed by the Israeli occupation in 1948 and 1967, you have the issue that the holders of the archive are in physical and economic survival mode. Caring for your archive is not the most important priority. This is the path we had to tread. Being selective while respecting the situation. We decided from the beginning — this is the fundamental criteria of selection in the strategy — to focus on microhistories and “history from below.” In addition, the project manager developed a set of geographic and thematic criteria to accompany this search for documents, criteria that attest to the achievements and steadfastness of ordinary Palestinians in Palestine and the diaspora, from the mid nineteenth century to the present. During the COVID lockdown, we also produced educational videos for social media to educate our public about caring for home archives, how to conduct interviews at home etc. Of course, the main difference of approach with my work on the Fahrelnissa archive is that in the latter, I was the researcher benefiting from the archive and judging what was useful from the un-indexed material to help me re-form the world and life of the subject studied. The archive itself remained private and closed, and what emerged to the public was my book. Our task with the museum’s digital archive was rather a preservation and publicizing endeavor: safeguarding an archive and giving it to the world, the public, future researchers, without edits, mediation, or interpretation. So, both were very interesting -albeit different- intellectual and historical positionalities.

DO YOU KEEP THE PHYSICAL COPY OF THE ARCHIVE OR NOT?

No, we did not. We would find a given collection, agree with the owner, survey, and index it. If we decided it was relevant material, we archived it, digitized it, added the metadata, uploaded it, and then returned the items to the owner with a digital copy. And, of course, no money was exchanged There is another service we performed at the Museum’s paper restoration lab: A lot of the archives we received were in bad shape. So, before they were digitized, we restored them. The owners got back their collections, preventively restored, plus a digital copy.

IT SEEMS A FAIR USE OF THE ARCHIVE OF PEOPLE THAT YOU CARED FOR.