NADA SHABOUT

ART HISTORY AS AN ARCHIVAL PRACTICE

Abu Dhabi, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

Dr. Nada Shabout is a Regents Professor of Art History and the Coordinator of the Contemporary Arab and Muslim Cultural Studies Initiative (CAMCSI) at the University of North Texas. She is currently a Visiting Professor of Art History and a Senior Investigator at al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of art at NYUAD. She is the founding president of the Association for Modern and Contemporary Art from the Arab World, Iran and Turkey (AMCA). She is the author of Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, 2007; co-editor, New Vision: Arab Art in the 21st Century, 2009; and Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, MoMA, 2018. Curator of All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, Hessel Museum, Bard College 2025; A Banquette for Seaweed: Snapshots from the Arab 1980s, 2022-2023; Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, 2010; Dafatir: Contemporary Iraqi Book Art, 2005-2009; and co-curator, Modernism and Iraq, 2009. Her awards include Getty Foundation Grant in 2019, Andy Warhol Foundation 2018; The American Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TAARII) fellow 2006, 2007, Fulbright Senior Scholar Program, 2008. She received the Presidential Excellency Award, UNT 2018 and the 2020 Kuwait Prize for Arts and Literature from the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. Shabout is on the Founding Board of Directors, Visual Art Commission, Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia (2020-2023, 2024-2027); the Board of The Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TARII) 2013-present; and the College Art Association (caa) Board of Directors (2020-2024).

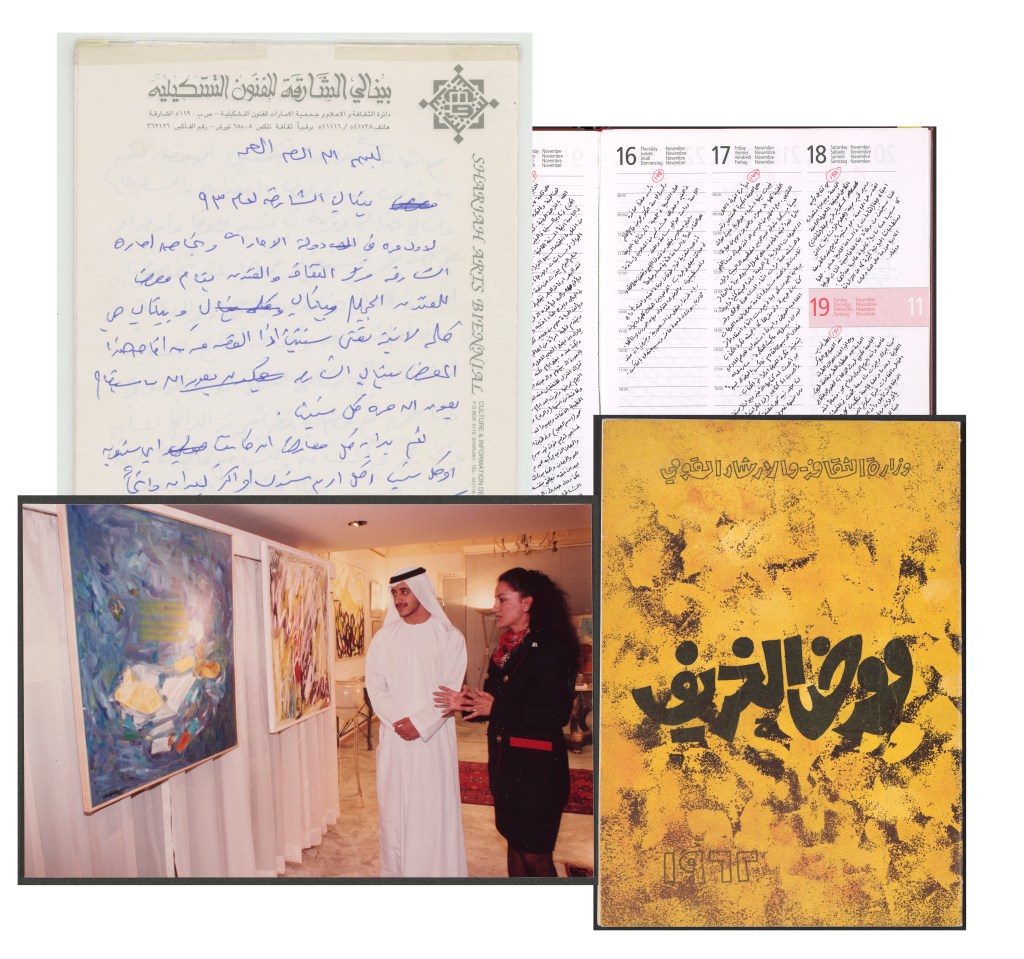

the Arab Art Archive. From the Arab Art Archive, al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art, New York University Abu Dhabi.

DR SHABOUT, WHAT IS YOUR DEFINITION OF AN ARCHIVE?

As an art historian, archives to me are voices from the past. They are records of primary documents (newspapers, diaries, manifestos, letters, photographs, etc., both personal and public) that allow us to enter into that period of time and understand the thoughts and work of art better. As well as being objects of art, works of art are also documents of sort. The metadata surrounding the production of the artwork -personal, cultural and socio-political- supports our understanding of these objects of art. They provide the larger context necessary to write our narratives and stories. While at times these archives feel like precious commodities and beautiful objects in their own rights, my relationship with archives is empirical and practical.

HOW ARE ARCHIVES PERCEIVED AND USED, PARTICULARLY IN THE ARAB WORLD?

Without making the assumption that art history is or should be what we practice in the Euro-American world, we have very little in the form of contextual narratives of secondary documents about the art in the Arab world. There could be a number of reasons as to why Arab artists have not felt the necessity to document in the form of writing an art history. The case was similar in the Islamic world as well. Accounts of Islamic art history were written during the 18th-19th century in Europe when the whole field of art history was invented. Thus, for example, when James Elkin asks if art history is global, meaning does it have the same recognizable form as we understand it wherever it is practiced, the question goes beyond art history to an understanding of value of the visual and how it is understood and appreciated. It speaks of methods and concepts, as well as perspectives. That we expect it to be recognizable, speaks to the canonical hegemony. However, the lack of historical accounts on art and its production in the Arab world, along with an increased interest in the modern and contemporary arts of the Arab World, made the need for the field’s historiography vital. As it stands now, it seems that this historiography is being developed mostly in the diaspora and in different foreign languages. The imbalance of this situation prompts inquiry into the state of the discipline of art history in the region. For this reason, the Association of Modern and Contemporary Art from the Arab World, Iran and Turkey, AMCA, launched a project of Mapping Art Histories in the Arab World, Iran and Turkey, funded by a grant from the Getty Foundation, Connecting Art Histories initiative, and in collaboration with the University of North Texas. The goal of this project is to generate information about the many ways in which the history of art and design as well as visual culture are taught in the region. By contextualizing the preferred pedagogical methods in art historical education within the broader framework of culture and politics, the project aims to present the most comprehensive database possible. This information is openly accessible to scholars, researchers and students working on art histories of these countries or those who want to have a better understanding of a global art history. The still in progress, accompanying website (amcamappingmena.org) maps the teaching of art history in official institutions and universities, as well as alternative and informal programs. More importantly, it provides data that allows for a better understanding of how art history is perceived and how art historiographies in the region are developed. It will allow for an analysis of the disciplinary implications for delimiting how “Art History” is constituted in the region. While largely approached as a discipline in Euro-American institutions, the innovative interdisciplinarity of “Art History” in the Arab world, Iran, and Turkey would offer new understandings of the art historical “discipline” at large. In turn, this will enable art histories of the region to account for new paradigms for the production and reception of modern and contemporary art, enabling responsible and effective studies of art outside Euro-American centers. In order to speak of a globalized art history, we must attend to differences in the study and training of the discipline itself. To aid the region in writing its historiography, archives are all the more important and needed. They are the legacy of the past for contemporary societies. They have the power to subvert dominant and mainstream narratives by showing different factors capable of challenging the current historiography.

COULD YOU ARTICULATE THE NOTION OF FRAGILITY AND NECESSITY OF THE ARCHIVE IN POST-CONFLICT COUNTRIES, SUCH AS IRAQ?

With decades of isolation because of government oppression and sanctions, with all the destruction that followed the wars in the last three decades, and particularly the 2003 US-led invasion, Iraq has been suffering from deliberate memory, identity and historical erasure. There are now two generations of Iraqis who only know Iraq as a ruined country. They do not know the accomplishments and legacies of their past because the evidence of it all has disappeared! Archives will not only tell them who they were and who they could be, but also show them a way out of some of the challenges they face today that were also faced in the early 20th century. For example, the predominant rhetoric used today in relation to Iraq as an incoherent country with its diversity was also that of the 20th century as promoted by British imperialism when the country was first established. The diversity of the country, however, apparent in works of art produced by Iraqi artists, as well as in their conversations, expresses excitement and hope. Iraqis could really use some hope today. Iraqi artists in the twentieth century were active participants in forming the notion of what it meant to be Iraqi. They were part of the national formation and the establishment of an inclusive social consciousness. In many ways, the national existence of the country depends on its people’s knowledge of this history.

HOW MUCH DOES THE LACK OF LIABILITY OF THE ARCHIVAL SOURCES ON MODERN ARAB ART AFFECT ITS RECEPTION IN AND OUTSIDE THE REGION? SHOULDN’T ANOTHER PARADIGM BE FOUND, AND IF YES, WHAT ARE YOUR INTUITIONS AND THOUGHTS ABOUT THAT?

When I started my research on Modern Arab art, I encountered a simple linear narrative of how the Arab world discovered and learned modern art. This narrative has been based on few interviews and articles published during the second half of the twentieth century. Archives did exist but were not easy to find or access. However, things have changed tremendously since then. The digital age and social media have opened up new doors. For example, while preparing for the Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Document (MoMA, 2018) publication, my co-editors (Anneka Lenssen and Sarah Rogers) and I held two workshops, the first with artists, gallerist and scholars who were active agents in the art scene during the mid-twentieth century. From them we learned about other resources that we were able to trace and access. The second workshop was with scholars working on different parts of the region. It was a challenge to access and clear permission for many of the archival material we trailed. Nevertheless, at the end we were able to translate 127 texts that covered the region for about 100 years, ending in 1980. The project certainly dispelled the myth that there are no archives for art in the Arab world.

Archival knowledge is extremely important. What we found allowed us to chart the path for new methodologies to understand the aesthetics of the Arab world. That would also be the way to deconstruct Eurocentric canonical hegemony. But more importantly, it would allow us to tell different stories that are specific to the time, geography and people.

IN YOUR OPINION, WHAT DO YOU ARCHIVES NEED TO BE SUCCESSFULLY UNFOLDED? COULD YOU DESCRIBE THE MOST RELEVANT INITIATIVES THAT YOU CONCEIVED TO MAKE THEM ACCESSIBLE AND, THEREFORE, EXIST? I’M THINKING ABOUT THE MODERN ART IRAQ ARCHIVE, IN PARTICULAR.

Archives are only useful if accessible. They contain potential knowledge that you can only gain by being able to work with them. And they are of course open to interpretation. To write the history of any country, scholars need access to documents. I established The Modern Art Iraq Archive (MAIA), located at http://artiraq.org/maia/, as a last resort to counter the destruction of Iraqi culture, heritage and art. When all my other efforts to find the lost works following the US-led invasion in 2003 failed, I hoped their traces in the digital form and in documenting them would provide the evidence of their existence. MAIA, thus, started as the result of a long-term effort to document and preserve the modern artistic works from the Iraqi Museum of Modern Art in Baghdad, most of which were lost and damaged in the fires and looting during the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq. As the site shows, very little is known about many of the works, including their current whereabouts and their original location in the Museum. The lack of documents about modern Iraqi art prompted the growth of the project to include supporting text. The site makes the works of art available as an open access database in order to raise public awareness of the many lost works and to encourage interested individuals to participate in helping to document the museum’s original and/or lost holdings. The aim of MAIA is to map out the modern art’s development in Iraq during the twentieth century and be a research tool to scholars, students, authorities, and the general public, as well as to provide evidence of the rich modern heritage of Iraq. Furthermore, the creation of an authoritative and public inventory of the collection will not only act as a reminder of their cultural value and thus hopefully hasten their return and prompt restoration and documentation, but will help combat smuggling and black-market dealings of the works. I wanted Iraqis and scholars to be able to get access to these documents, and hoped the interest would generate further research and studies. Archives need to be open and accessible for all interested, specially scholars, in order for them to generate knowledge. Digital platforms have proved their usefulness. I encourage everyone who has access to archives to find a way to share them.

Another example on an institutional level is Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. As the only institution of its kind, with a large collection of modern works from the Arab world, from its inception Mathaf had the potential of serving as an archival hub and research institution. Understanding and caring for the collection of works from around the Arab world, dating from the late 19th to the contemporary, in itself necessitated contextual knowledge in order to develop needed data for the registrar and conservators. More importantly, having the collection allowed for writing narratives based on what the works as an archive tell us as opposed to writing about them from afar. In other words, it allowed for subverting and decolonizing the cannon by decentering modernism from the European perspective, and developing more relevant methodologies. The framing of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art is directly connected to the notion of representation by virtue of its name and ideological mission to contest the art historical canon from which art from the Arab world has been excluded. While Mathaf’s vision proposes a regional cultural unity, it equally provides spaces of difference to understand connections, intersections and overlaps between the regional artists.

The inaugural exhibition, Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art, that I curated, initiated a strategy of contextualizing new narratives that negotiate different regional possibilities for the formation and development of modern art of the Arab world and its diasporas. The exhibition proposed a global discourse that historicizes Arab modern art within a wider tradition of art history and extended a narrative that challenged the simplistic one of colonial confrontation leading to uncritical imitation of European art; a narrative that has been accepted as the official story of modern art of the Arab world. The curatorial premise of Sajjil did not assume a singular or unified Arab experience but projected the multiplicity of experiences that nevertheless, often intersected and overlapped and shared several-common moments of real and imagined history and collective identities. This was particularly true to art made in response to shared senses of anticolonialism and Arabism, which communicated similar objectives, not unlike the visual production of the last years in response to revolts and regional uncertainties. Sajjil reevaluated the role of identity in the arts from a global perspective instead of further marginalizing that of Arab art.

Following on from my earlier work, Sajjil introduced a rereading (or construction) of modernism of the peripheral within a globalized context that frees Arab art from the confines of identity politics without denying their effects on its formation. Accordingly, it opened a space to unpack, confront and interrogate, among other problematics, regional historical continuity, what it meant (means) to be an Arab artist and how such meaning was (is) articulated through the visual. On a more mundane level, it tackled the problematic of how should Arab art be approached methodologically and practically. Explicitly, and most importantly, the exhibition perceives the story of Arab modern art as a discursive formation that embodies cycles of discontinuity and rupture as part of the discourse. It necessarily refuted the dominance of the Euro-American canon of art history with its isms and categories as the ideal model.Sajjil was a beginning that posed many questions. It confirmed that much research is needed to fill the gaps of what has traditionally become accepted as a major rupture in the cultural history of the region causing debilitating stagnation. It seemed quite arrogant to imagine that such rupture created a complete historical and creative black out. The 18th and 19th centuries inextricably hold much potential for missing links in our narratives. It is within the localities of these centuries and their possible dislocated temporalities that we must search for the emergence of the Arab modern moment. Thus, was the need to start the short-lived research centre for Arab modernism that promoted archival research and scholarship. One of its main initiatives I initiated and that continues today under new guidance is the Encyclopaedia of Modernism and the Arab World. Among the goals of the bi-lingual and peer-reviewed entries of the encyclopaedia is to represent artists’ biography within a wider appropriate and relevant context, while correcting data information as well. Scholars writing these entries identified and shared archival resources. It thus serves as another venue of sharing and producing knowledge.

HOW DO YOU KEEP AND USE YOUR PERSONAL ARCHIVE AND WHAT FOR? WHAT’S THE FUTURE DESTINATION OF IT?

At the moment, I have physical archives kept in my office while I share digital copies on MAIA. I know many of my colleagues who research art in the region do the same. My hope is for an institute that would take them and share them both digitally and physically. They need to be accessible to all. The Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Document, MoMA 2018 book was not only meant to provide access to some archives but also to start these conversations about what to do with our archives. We at AMCA have been thinking about some digital possibilities. Currently, the important platform of al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at the University of New York Abu Dhabi (https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/research/faculty-labs-and-projects/al-mawrid.html) is essentially revolutionizing the concept and access to Arab art archives. Initiated by scholar Salwa Mikdadi, al Mawrid has established new archival practices and vocabulary relevant for Arab art. Its potential is limitless. Along with providing access to high quality digital and complete data for the artists it represents, al Mawrid has been acquiring complete sets of important journals and publications from the Arab World. As an important reservoir for data and material, through interaction with scholars, fellowships and publications, it is a reach center for new narratives and historiographic frameworks. I have already promised them my archives.