SOL HENARO

ARCHIVE AS FREEDOM

Mexico City, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

Sol Henaro bets on the generation and intervention of micro narratives ‘inside the fold of memory’. This interest had an impact on her teaching, academic and curatorial actions. She curated more than 30 exhibition, among them: No-Grupo: Un zangoloteo al corsé artístico (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, 2010) and Estados de Sitio (Trienal de Chile, 2009); Pulso Alterado, Intensidades in MUAC’s Collection in collaboration with Miguel López (MUAC, 2013); Melquiades Herrera: el Peatón profesional (Celda Contemporánea, Mexico City, 2004) and Perder la forma humana, una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta latinoamericanos (Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2012) as part of the research group Red Conceptualismos del Sur, which she is part of since 2010. From 2011 until the middle of 2015, she was in charge of curating of the Artistic Collection of the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City where, since 2015, she has been in charge of curating the Documental Collection and responsible of the Arkheia’s Center of Documentation. Since 2014, she has held the position of Director of the Museo Universitario del Chopo in Mexico City.

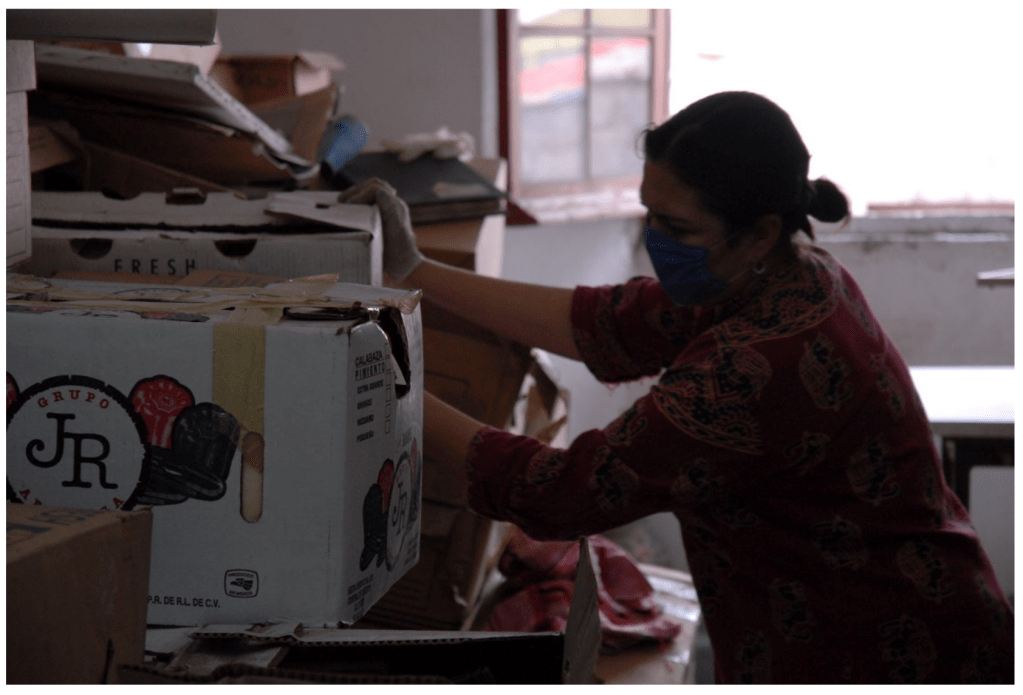

Exploration of the Melquiades Herrera Collection at the Antica Accademia di San Carlos, 2009. Credits: Sol Henaro

WHAT IS AN ARCHIVE TO YOU?

I understand the archive as an accumulation of heterogeneous materials that an agent — individual, collective, institutional, or independent — can gather as part of an impulse, a research, or an affection. It functions as a map for weaving relationships, drifts, and meanings among the elements and the subjects that comprise it: a kind of ontological index with multiple readings and possibilities. Summoning Deleuze and Guattari, I understand the archive through the conjunction and, and, and… to establish infinite conversations.

WHAT’S THE ROLE OF ARCHIVES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETIES?

In the past, it was natural to think of the archive in a reductionist way, as part of a common legacy related to public administration and academic objectives. Today, its potential is recognized through a diversity of practices and perspectives, including those emerging from extended artistic communities. Its role is fundamental to the politics of memory, as a sign of information rights and common heritage — something that should not merely be sheltered and preserved, but above all, made available to others, so that through this access, it can have an impact or reverberation in the present.

AND, MORE SPECIFICALLY, IN MEXICO?

In Mexico, over the past fifteen years, several unprecedented initiatives have emerged and strengthened as commissions of exploration, research, and activation. We can point to earlier projects that acted as catalysts, emphasizing the importance and urgency of articulating memory. For example, Pinto mi Raya — an independent project founded in 1989 — began forming an archive in 1991, which is now considered a point of reference.

Meanwhile, within institutional museum contexts, Ex Teresa Arte Actual undertook one of the first efforts to organize documentation and prepare an archive on the action art scene in Mexico. On the one hand, these initiatives stemmed from the desire to make information public and preserve it; on the other, several artists and collectives from the 1970s and 1980s also created significant archives driven by their own need to organize and make sense of materials that, at the time, many institutions and art professionals did not know how to support.

Groups and artists such as No-Grupo, Proceso Pentágono, Maris Bustamante, Melquiades Herrera, and Felipe Ehrenberg are perhaps the most well-known examples — they created exceptional archives that are now available to anyone interested, forming part of a broader network of repositories. Archives allow us to read the past in order to understand the present; they are essential.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM ARCHIVES, SOL?

Fortunately, we live in a time when archives exist, are discussed, and inspire politics around their existence. I recognize the impossibility of “bringing everything together” — the fantasy of a complete repository is a schizoid illusion. Yet, it is also true that initiatives are multiplying, and a critical gaze is spreading across them.

Access to archives allows us, among other things, to complicate historiographical narratives, to defend certain micro-narratives, to destabilize established arguments and myths — and, ultimately, to remember that stories are neither stable nor permanent. The archive is political. For me, its relevance lies in its ability to shake inertia and destabilize dominant narratives. I can’t imagine working on memory politics without archives.

I ALWAYS ASK: WHAT DO CURATORIAL ARCHIVES NEED TO BE SUCCESSFULLY UNFOLDED? IF THEY NEED TO BE UNFOLDED…

I’d summarize it in one word: porosity. There is no such thing as “one model” of an archive, nor could such a model be applied universally. Each archive must be read in its own singular way, and to be unfolded, it must be thought of accordingly.

As with all research, working with archives requires managing desire — not everything must, or can, be exhibited. A certain economy must prevail regarding what to highlight or make visible amid the vastness of the repository. There are no minor documents. The key lies in sustaining a political, playful, and/or experimental gaze toward the archive — in provoking a rupture that seduces or challenges without excluding anyone.

We don’t want to simply unfold archives or develop soporific approaches; our desire is to unfold them sexily. I find it particularly irritating when someone claims that archives are only for “meta-specialists” — such a stance feels entirely outdated and sectarian.

WHAT’S THE FUTURE OF CURATORIAL ARCHIVES, IN YOUR OPINION?

I hope we can soon blur the distinction between artistic and documentary collections, so that both are valued equally as part of our shared heritage. In this sense, I am excited by the idea of public and private museums acquiring archives as part of their collections — activating them through public, academic, and exhibition programs for diverse audiences.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, we discussed internationally how to make archives and collections accessible remotely. In that period, I often reflected on the image of a restricted or aseptic archive.

ABOUT YOUR ARCHIVE…

Rather than speaking of my personal archives, which certainly include research and curatorial work on practices from the 1970s to the 1990s in Mexico, I prefer to emphasize how I’ve transferred that interest into strengthening and professionalizing a public repository that contributes to collective memory and serves multiple users.

Honestly, moving from being curator of MUAC’s artistic collection to curator of documentary collections at the Centro de Documentación Arkheia was one of the best professional decisions of my life. I’ve been working with memory politics for 18 years, but the possibility of intervening in historiographic micro-narratives is both a privilege and a great responsibility.

I understand my position as a political strategy tied to memory, an opportunity to liberate different memories within the public sphere. From there, I’ve continued research to locate, preserve, and submit archives as part of a public university heritage, a crucial political operation to prevent these archives from being dispersed, fragmented, privatized, or lost.

I SPOKE WITH MANUEL BORJA VILLEL ABOUT RED CONCEPTUALISMOS DE SUR, IN THE FIRST VOLUME OF INTERVIEWS… IT IS, DEFINITELY, ONE OF THE MOST INTERESTING INITIATIVES. TELL ME MORE ABOUT IT. YOU ARE PART OF THE NETWORK…

I’d say that the collective work we support, Red Conceptualismos del Sur, of which I have been a part since 2010, shares a desire to think about memories and archives as a common good, something urgent, and to work collectively and in a decentralized way to sensitize, politicize, and professionalize them in different contexts, in order to break through the inertia of institutions, colleagues, and the general gaze (starting from their indifference) toward archives.

What connects us is our interest in a critical historiography that recovers and returns to the public sphere discussions and practices we consider urgent, and that continuously reflects on the timeliness of the archive, its potential, its fragility, and, above all, the urgency of caring for it.

THEN LET ME ASK YOU AGAIN… ABOUT YOUR ARCHIVE?

My archive is a lair, a burrow inhabited by many. I return to it whenever I feel the need, but I also open and share it with others when they ask. The zeal for hoarding knowledge or archives annoys me.

For example, the material I’ve collected on Melquiades Herrera and No-Grupo, to whom I’ve dedicated many years of research, I do not consider confidential. Like the members of Interference Archive, I believe there is no better preservation for archives than their use, so that they continue to generate new narratives, critiques, research, and exhibitions.

Eventually, as long as Arkheia accepts it, I plan to donate my archives to MUAC, to continue their life alongside the other 54 archives currently housed there. Archives without use lose their potential, they must be opened up.

WHAT’S YOUR RELATION TO IT?

Since 2015, I’ve dedicated myself to assembling archives for the public memory of MUAC’s collection at UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). I’ve witnessed both the indifference of some heirs toward documentary collections and the almost obsessive attachment others display toward them.

Before seeing myself as someone affected by Diogenes syndrome, I’d rather ensure that the repositories I’ve lovingly built as part of my work find new life through public access. The idea of “zombie archives” has never appealed to me.

For me, the opportunity to nurture and professionalize a public repository within a contemporary art museum — MUAC’s Arkheia Documentation Center — is pure adrenaline and stimulation.

My own archive, and those of other people, groups, and initiatives that I’ve studied or incorporated into MUAC’s documentary collection, resurface constantly — in the courses I teach, academic events, curated exhibitions, systematic mappings for new acquisitions, and in the many informal and formal consultations I engage in, as well as in research projects developed with Red Conceptualismos del Sur. The archive is always present. It’s part of my language, my way of engaging with the world.

Since the late 1990s — though, of course, I’ve become more professionalized over the years — I’ve had many formative experiences, like in 2003 when I got a severe eye infection after reviewing Felipe Ehrenberg’s archive. I recall fondly my obsessive-compulsive effort to locate, reassemble, and reintegrate the archive of the non-object artist Melquiades Herrera into the public sphere — a task to which I devoted about twelve years until it became part of MUAC’s collection. In 2018, I wrote a short text about that experience titled “Periplo de una inscripción” (“Periplus of an Inscription”).

HOW DO YOU IMAGINE YOUR PERSONAL ARCHIVE TO BE USED AND/OR ACTIVATED BY YOU, AN INSTITUTION, OR A THIRD PERSON?

I hope that archives can be embraced, read, activated, and used according to their potential for action, and, above all, their capacity for freedom.