ALA YOUNIS

ARCHIVING WITHOUT TAKING NOTES

Istanbul, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

Ala Younis is an artist with research, curatorial, film, and publishing projects. Younis’ projects are expanded experiences of relating to materials from distant times and places; working against archives play on predilections and how its lacunas and mishaps manipulate the imagination. She collaborated with Arsenal Film and Video Art Institute on researching, programming and publishing on several film archives and collections. She has presented her work in solo exhibitions across Amman, Dubai, Sharjah, New York, London, Seville, and Prague. She curated several shows including Kuwait’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2013). She was co-Head of Berlinale’s Forum Expanded (2021-2024), co-Artistic Director of Singapore Biennale (2022), Artistic Director of the Akademie der Künste der Welt (2023–2025), and Artistic Director of Darat al Funun – The Khalid Shoman Foundation (2008–2010). She is co-founder of Kayfa ta, an independent publishing initiative that organized exhibitions and publishing as artistic practice, at Beirut Art Center (2019), Warehouse421 Abu Dhabi (2019), MMAG Foundation, Amman (2020), and Kochi Biennale (2022). Between 2022 and 2025, Younis contributed to the foundation, research work, and building of digital archives on Arab art, via al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at New York University Abu Dhabi.

Credits: Ala Younis.

YOUR WORK WITH ARCHIVES HAS ALWAYS FASCINATED ME. I WONDER WHAT AN ARCHIVE IS TO YOU?

The remains of relations, recessions, ascensions, fears, fondness, access, excessiveness, (in)abilities, chance encounters, and forgetfulness. It is a host of multiple worlds comprised of minute particles that vary (with time) in their importance, meaning and accessibility.

WHAT’S THE ROLE OF ARCHIVES IN THE ARAB WORLD?

A set of notes to myself produces a partial cartography of the art institutions of the Arab World; it cannot but point out where institutions are absent, self-made or temporary. Such notes remember exclamations on vague futures, expressed by artists at moments of fear or fragility. The same fragile fate puts the region’s attended and unattended projects and collections at the mercy of informants, violence and chaos. Meanwhile, many individual practices function as institutions in effort to provide infrastructures that would allow them to harness their energies as part of the broader debate on the fate of cultural production and collections in the Arab world.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM ARCHIVES?

In my research, I attempt to reconstitute archives of unattainable eras, based on images imprinted in memory, spoken words, selected chapters or sentences from publications or films, and from encounters that allow revisiting them several times for different interpretations or examinations. In the curatorial and research activity, we attempt to establish relations between what we know and what we are curious about. There is a mutual support between working as a curator and my artistic practice; I am collecting stories, objects, impressions and future projects as I am also putting together a show or a film program or editing a publication; in other words, I am answering questions that I have and feel they resonate with some elements in other people’s artistic or scholarly work.

The results are often a morphing constitution of many elements from different geographies, practices and times. Whether physically or conceptually, the processes of thinking and rethinking beyond the surface or known aspect of a found material, and linking them through research threads turns them into a temporary archive… the most enticing. I cherish as my personal archive the materials these temporary gatherings, as well as the most ambiguous parts of this process, sometimes a sole image that can find no place in the presentation, or several reproduction sketches of a trace of relations that still cannot unfold, screenshots that are difficult to name, html pages saved in fear of links going offline, dusty publications that belong to others, stamps that travel inside envelopes not on them, and/or objects that have lost some of their parts. But what about a voice or background noise from an interview, a feeling of awe after entering a space, fear or excitement upon meeting a certain document or piece of information, things we regretted saying, or protagonists who refused to be recorded… these are threatened sensorial archival collections: what remains in memory, what can be activated without going back to the archives, what is not captured in physical or ethereal recordings. These archives are as precarious, fragmented and threatened as the content that gradually fades in the mind.

WHAT DO ARCHIVES NEED TO BE SUCCESSFULLY UNFOLDED, IN YOUR OPINION, ALA? WHAT ARE THE TRACES YOU PERSONALLY LEAVE IN THEM?

I was visiting architect Rifat Chadirji in his residence in London in 2018, when I tried to quickly find a pen to note down something important he said. He eased this urge by confirming to me that if I attempted to understand what he was saying then I would not need to write it. It can be a challenge to listen, understand and remember, mostly also because one is carried away by her own thoughts when listening to stories. But this came from another sense a couple of days later, when I was sitting with architect Wijdan Maher: she refused to let me note down details related to her work as she was answering some of my questions. She said I won’t need to write down because I won’t use this info in the future! What I learnt that moment was that I am there not for the factual info, which I could also get from somewhere else, I was there for the encounter to inform on something that is difficult to trace without human interaction. I cannot formally reproduce that hesitation but understand the obstruction of the document was her decision on what is to be recorded. We often find gaps in archives and speculate about the reasons that produced them, and here I could witness the moment of producing such a gap. I try to deposit indices and traces on these archival journeys in written texts that also expand on the emotions, contexts and personal decisions that relate to the curatorial and artistic choices that I have made. When these texts are published in other platforms and publications, they exist in a more communal space than that of my library or studio, and perhaps parts of them become part of an alternative archives, or a critique of one.

CAN ARCHIVES SURVIVE OUR TIMES?

Besides the fragility of collections in jeopardized areas which continues to be the context and environment of our work in the region, the question on the future of archives is related to the transformation of property that happens in the process of curatorial and research activity: while we generate intellectual ownership over approach to stories and elements that we identify, we also face the dilemmas of owning our images and stories (or comprehensions) in the archives of others. Archives in general are protected yet crippled by ‘legal’ inheritances that obstruct our sub- or co-ownership of them, copyright laws are enforced to protect against financial exploitation, while also obtaining value to this inaccessible or difficult to reproduce content. Some materials now are destined to cool closets while they are reproduced as digital impressions the reproduction of which is resold again to people of interest. The curatorial projects allow access (even if partial) to these materials and in some cases, visitors take photos of them and these impressions start to exist in other, more organic collections. I think there is a downplayed aspect of futurity in here. Just like what Chadirji advised, there is a potential of reproduction that is not related to the physical recording but rather of understanding where these archival elements fall in our own history and web of relations. Together we think of other ideas (beyond intellectual and estate ownership) for dis-owning and re-owning the voices that these objects could speak in.

COMPLETELY. AND IS THERE A DISTINCTION BETWEEN ARTISTIC AND CURATORIAL PROJECTS, IN YOUR ARCHIVE?

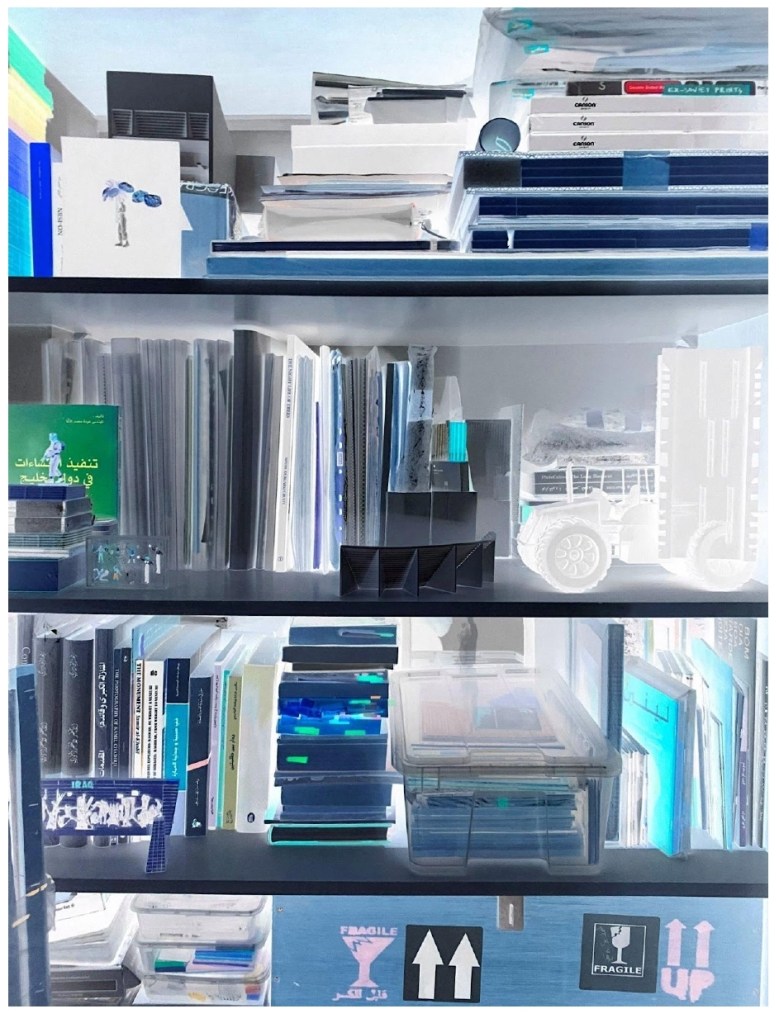

At age of 10, I moved with my family from Kuwait to Jordan. Palestine, Egypt, Syria and the US became closer key places (not necessarily physical but certainly cultural) in my upbringing. Iraq to me was a state at war all the time (from the images of desert battles and war prisoners that we saw on TV); but, from 1990, it became very influential to what and how we lived in Jordan, and so were the expats expelled from Kuwait. The peace agreements and the rise of gulf cultural values necessitated an unlearning and another re-visitation. We also moved between houses, schools and technologies. Each transformation required an adaptation of what we own, what we cherish, and the tone and medium in which we document (we had to transfer our moving images from super 8mm films to video tapes then to CDs and our feelings towards the events we were transferring were also changing). As I grow older, I re-meet the events of my life in a different way and in relation to other geographies. I learn (or forget) some details or become unsure of how to deal with aspects related to these events that I could only see or learn in retrospect. I think of the seepages, where these details and their materials (of books, images, songs, anger, and other) have leaked through. My archive is an attempt to deal with seepages, of those that evaded my attention or ran parallel to it. I realize and react to the scarcity and fragility of what could detail these histories to us, and so my archive is obsessed with collecting placeholders: as many as possible from the Arabic Soviet (children) books because there was a vague relationship to Soviet culture in the places I grew up in compared to the experience of my peers in neighboring cities, but I also collect an Arabized Swedish series, Palestinian publishers’ children books, besides materials published by or on political prisoners (particularly Palestinian freedom fighters) writings in prison, or unofficial stamps issued in solidarity or depiction in artworks or songs that weren’t allowed to travel on cassettes or models of their figures or literature related to them or to local (or art / hand drawn) textbooks or materials on middle-class labour or communist parties or on lending skills to other countries. I also collect materials on construction and contractors in third world countries plus every book I find on architecture or contracting in modern Baghdad or on/from the writing of Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gadhafi, or the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser and literature by other presidents, as well as educational props, illustrated drawings, maps and anthologies marked with readers’ handwritings (found ones marked by Stuart Hall). Disappearing artifacts, tin soldiers, sets of figurines for models, varieties of palm trees models and illustrations, lithography prints, books on printing, on old computers, and a variety of independent publishers’ work, and so on. This does not mean that I have the most extensive collections of what I mention, on the contrary, none of the collections that I have are comprehensive enough because they are bought or picked up in processes of researching, mostly parallel projects. I get these materials and organize them in my studio as multi-practical groups that speak to each other.

WHAT ARE THESE ARCHIVES TEACHING YOU?

Attempting to find the reasons and relations behind these compilations allows me to understand not just my own practice and interest in visual culture, but also the indices of movements and moments that have leaked into or shaped our societies. It is also helpful when explaining the conflicted geographies and ideologies that we feel we come from. Some of these materials transfer to my archive following an exhibition, other are collected during research and perhaps they are repurposed or reproduced in another format or merged with other stories in a new object to be presented in an exhibition, other materials are found or re-drawn from personal or family collections, and so on.

COULD YOU GIVE ME A FEW EXAMPLES OF INITIATIVES THAT ARE DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY LINKED TO THIS ARCHIVE?

What I accumulated for “An Index of Tensional and Unintentional Love of Land” which was part of “Here and Elsewhere” exhibition of Arab art at New Museum in 2014. I thought it was challenging to present a show to an audience whose knowledge varies from the expert knowledge to non-expert, and I wanted to mix artworks with ephemera that attempt to describe a relationship to a place, that could not be by choice or that required a subscription to its causes, but did so by focusing on the shared iconography that is purposed differently in each country. I collected matter that would stress a resemblance from the outside but explained locally differently. I made this through a tracing of the movement of Palestine throughout its geography and times. For instance, harvesting oranges in Jordan was caught on camera as part of its campaign in the United Nations to complaint against the Israeli aggressions post 1967, the same images are inscribed on the Moroccan currency as one of the symbols of national industries, while an orange is the second icon in a poster of fundamental Palestinian alphabets, illustrated by Mohieddine Ellabbad for Dar Al Fata Al Arabi (PLO’s children publishing project). While I do not keep the artworks, I kept most of the other materials presented in this presentation which can take a new rationale should it be shown again. Another example is the research outcomes of my work Drachmas (2019), which is an artwork that curates not only different Arab drama series but particular choices of scenes from these productions. This work draws on television stagecraft and the architectural vernacular of model making to consider the emergence of the Arab daytime TV dramas and the dramatic interplay of actors and events that conspired to shift centers of cultural production and political power. I looked into television Arab drama from the 1960s until just before the spread of satellite TVs early 1990s. The industry had quickly forged a network across the region and developed numerous genres set against backdrops of small village life, Bedouin culture, the glory of Islamic history, as well as ancient pre-Islamic times, espionage, the Palestinian resistance and solidarity, and the modern household and way of life. I collected scenes that are only inside studios: interior and exterior scenes were made from painting fake walls, installing props, making up actors, and putting up conversations. I was interested in how it was possible to produce a fake desert inside a studio and make a couple move down between its dry bushes, while spectators follow willingly on the couple’s conversation. The result of this research is not a presentation of the scenes but a 3D reproduction of how the exteriors and interiors in studios shaped our culture as they made way for large numbers of cast and crew not just to move between Beirut, Amman, Baghdad, Cairo, Athens, Kuwait and Ajman studios (just like how we travel for art events and research today). These scenes were meant to show how the series also managed to navigate war, evade boycotts, save small capital despite currency devaluations, and amass a great popularity, in a time that was continuously going through political predicaments. I created over 40 small-scale models based on scenes from well-known dramas, bringing viewers in for a closer look onto these issues. I chose for them to have a clinical look (white, simplified) and bought hundreds (but used less) of variety of miniature figures to install in the scenes. I was thinking I wanted ready-made figurines (just like actors they can be in other people’s sets representing other stories) and in my scenes, they present our relationship to specific social, political, cultural and geographic references, while highlighting the studio as a place of modest means but prolific production (also like my own studio).

DO YOU HAPPEN TO THINK ABOUT THE FUTURE OF YOUR OWN ARCHIVE?

There are endless ways to write about the forty years that I personally lived, but I am also interested in the decades that prepared me for my years, and certainly for those to come. I feel one secure future destination is a series of published indices. Small publications that can from one side present the collection as selections and expand on the relations that could be established between the selections. Such a process serves many interests: further explaining my work (to me before the readers), perhaps an attempt to theorize practices in relation to the local contexts these objects surfaced in, and contribute to or encourage others to piece some literature on these topics. As I mentioned earlier, I want to be interested in the knowledge that these objects can bring rather than their physicality (which I am also lured by and attached to). I have not yet thought of the future physical space that could hold these but just like I came to realize the importance of some of these materials, I am hopeful that they would meet some interested future researchers if deposited somewhere that fits.