HADEEL ELTAYEB and LOCALE

THE ARCHIVE AS RECLAMATIONS OF STORIES

Doha and Khartoum, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

Hadeel Eltayeb is a curator, writer and researcher. She is currently Curator at the Design Museum, London. Her research background is in socially-engaged art, museum and gallery practice, using oral history and explorations through sound as sites of research. She has curated exhibitions and produced research projects in Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Sudan and the United Kingdom. Exhibitions include The World is Watching Musalsalat in 2023, From Visionaries to Vloggers: media revolutions in the Middle East in 2020 and This Will Have Been: Archives of Past, Present and Future, co-curated with Locale Sudan in 2019.

Locale is a Sudanese female-led platform formed in 2016 that aims to develop and support the homegrown creative effort. Locale is a team of five, Aala Sharfi, Rund AlArabi, Safwa Mohammed, Qutouf Elobaid and Nafisa Eltahir, based in different parts of the MENA region. Locale designs, exhibits and collaborates with Sudanese artists, aiming to empower the Sudanese identity and preserve its culture. As a cultural influencer, Locale encourages local initiatives and challenges the creative community by promoting creative exploration and collaboration.

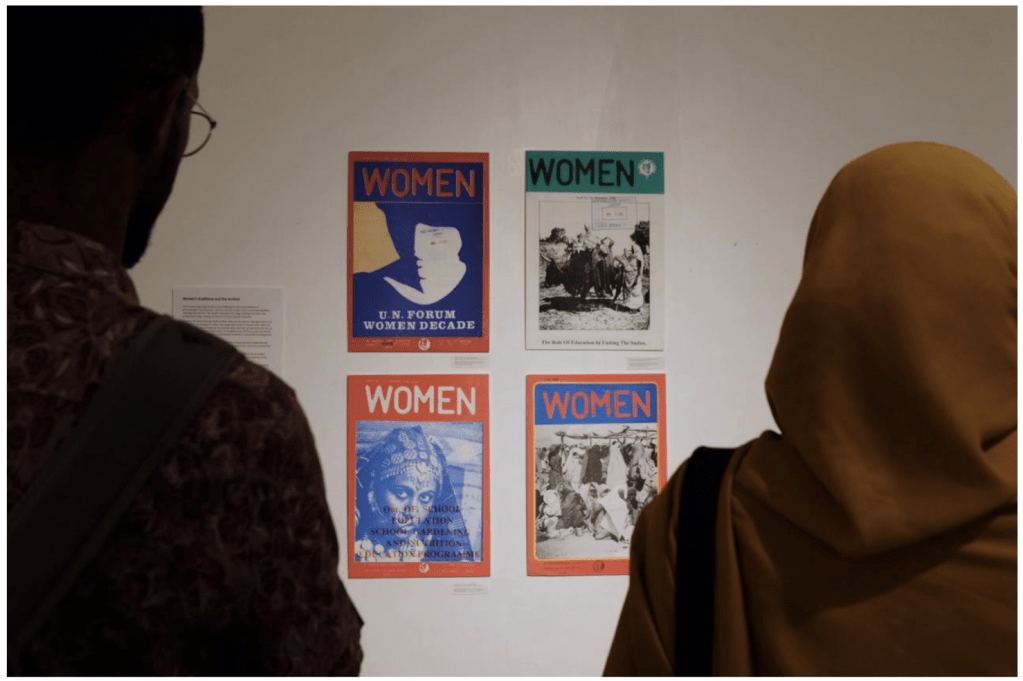

‘Women‘ Magazines (1985-1998) courtesy of Babiker Badri Scientific Assocation for Women’s Studies.

THIS DOUBLE INTERVIEW COULD, PERHAPS, ALLOW US TO REFLECT ON HOW TO OPERATE INDIVIDUALLY AND COLLECTIVELY, IN A SYNERGY, AROUND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES LINKED TO ARCHIVES. BUT LET’S START FROM THE BEGINNING: WHAT IS AN ARCHIVE TO YOU?

Hadeel: The themes of presence and absence resonate most strongly. In the context of museums and galleries, the curation of archives and narratives of ownership over culture is often an authorial voice, where history is presented as a monologue rather than a dialogue. Archiving as a process, both records and produces. As a curator, my responsibility lies in reflecting but not representing the voice of others, recognising the weight of legitimising some narratives and not others through the process of selection. My work has touched on the [in]accessibility of local archives in countries including Bahrain and Sudan, in projects that are socially engaged. In terms of my own curatorial archive, there is also the aspect of working as a curator within cultural institutions versus working as an independent curator, where the personal and professional overlap. The process of archiving changes meaning in both cases. I lose ownership of curatorial projects I create for larger institutions, in a way, and archiving past work becomes sterilised by record retention processes linked to insurance and licensing artworks. The curator is absent in those documentation processes. This makes the need for a curatorial archive more personal for me. Fieldwork is mostly ephemeral— fragmented in written correspondences with artists, post-its, photos, whatsapp conversations, international video calls and the notes app on my phone. I have folders in my laptop to map a project, but so many of them do not go as planned. We often expect exhibition publications to serve as an archive of the exhibition, but there can be ideological gaps and political aspects that limit what is possible to present.

Locale: Through our work, we have learned that the archive is any kind of history. It’s a significant and fundamental part of what creates cultures, and what helps us understand and examine them. It is literature, poetry, art, film, photography, and stories from our past that shape and inform our understanding of the present and future. The archive not only highlights narratives that need to be shared but also makes abundantly clear the narratives that have been excluded from the documentation. In working with Sudanese content, we have learned that personal and private archives hold just as much importance as institutional archives — which are in this instance much more accessible anyway — as they hold stories that are sometimes deemed unimportant and are much closer to the collector offering special insights. For us, the archive serves as a reminder of our role now, as creators, to be inclusive of narratives that may have otherwise been neglected, forgotten or intentionally removed. And through examining the multiple forms that the archive takes, we are able to understand parallel histories through more than one perspective.

WHAT IS AN ARCHIVE FOR? AND WHAT IS AN ARCHIVE FOR, IN SUDAN?

H: Archives are sites of memory. Oral storytelling practices are also indigenous to countries in the Persian Gulf, where I currently live and work, as well as Sudan, where I am from. Oral History interviews in their audio come closest to me as a valid archive in their richness, of the hope of a valid archive of curatorial work. This is because of the versatility of Oral History as a research tool as well as a research product, in order to form and shape ideas. Outside their broader sense of recording conversations for posterity, audio contains utterances that reflect pause, tone, emotion and tangential moments that would be removed from a transcript. I recalled in the notes for Locale publication Hunak, working on editing an oral history transcript for publication, the limitations of the written form: “In many ways, if this virtual exchange between the two of us is a form of historical record, it is fragmented and full of discontinuities, between his language and mine, his voice and my recorder, an audio recording and its flattening in a written transcript through which it loses even more of its context, like a copy of a copy.” The raw audio can be revisited again and has the possibility to take me to the moment in the past that ideas took shape, but also allows me the possibility to reshape them further into new ideas. In the case of the exhibition I co-curated in Sudan, I believe that the act of sharing stories, via historicized and contemporary rituals such as the folk songs and poetry created by Sudanese women, is an intervention of sorts on the historical record. In art communities we have now started to become accustomed to questioning the validity of archives, as public and private sites of memory and interrogating the means of production. Personally, this is why taking part in the exhibition, This Will Have Been: Archives of Part, Present and Future, and why oral history and exploration of music in the context of knowledge production, felt very significant. Collective ownership and a shared commons is a power dynamic more intuitive to African societies; we were highlighting how women in Sudan have long driven social change and created through oral storytelling, poetry and music were already part of the cultural canon. This knowing is a challenge to existing archival representations which are constructed through Western European power structures, which once threatened to make past cultural traditions and these intricate networks of shared knowledge and collaboration invisible. We hoped to show encounters with sound cultures and oral archives are more accessible than people may think, and they can be activated through various modes of analogue and digital communications.

L: The archive stands at the centre of the collective memory of a society. Its power lies in reminding people of their agency and in notifying them of the effects of certain historical events on their everyday life and the reasoning or meaning behind traditions, rituals and practices that remain in place today. Our objective, and what we saw as the role of creating an exhibition around the Sudanese archive was to turn attention towards a conversation that was long overdue regarding erasure and the importance of documentation; learning from our past while archiving with the future in mind. It just so happened that our latest archival exhibition in Khartoum This Will Have Been: Archives of the Past, Present and Future was held in the aura of a new future for Sudan, after the revolution which overthrew a thirty-year dictatorship. Exhibiting this content in this light, reinforced the idea that the archive will always serve that role; a lesson, a reminder, and a driving force for more diligent and inclusive documentation. The archive in Sudanese society is confrontational in the sense that it forces us to look at, and revisit, historical moments in our time and reconsider our beliefs about said events. As Hadeel has mentioned, oral histories dominate much of Sudan’s accessible historical documentation. Even within online spaces where a lot of cultural production takes place, documentations of oral history are visible as it is a very specific feat of Sudanese cultural practice. It is how we learn in our daily lives, and how we learn our histories, our traditions and family trees and where we come from within Sudan and, even on a grander scale, within Sudanese diaspora. The archive has also continued to be a mean of resistance to authority and authoritarian propaganda that worked relentlessly on destroying records to erase and dispose of an inclusive Sudanese identity, in order to remain in power. Throughout the last few decades, many books and films in Sudan were banned, musicians and artists were outlawed as an attempt to destroy parts of our history that threatened the regime. So, the archive in that sense can be viewed as a reclamation of those stories, quite literally speaking truth to power.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNT FROM ARCHIVES? ESPECIALLY FROM ARCHIVES OF YOUR OWN EXHIBITIONS?

H: Exhibitions are not neutral spaces, and through the curator’s role, like archivists, we have assembled stories and produced a narrative. These narratives have a sense of permanence and can become even more fixed in the hands of larger cultural institutions, and embedded within their respective political, social and economic context. The corporate culture of working ahead of deadlines, investor’s buy-in, working to budgets and producing deliverables is very much future-oriented and looking back wastes valuable time. Other projects present a more agile kind of curatorial archiving, outside of record-keeping and project management, that is temporal and imaginative. Time is a resource, and the personal archiving process can be an important tool in revisiting decisions, oftentimes, in the event we later discover things didn’t work out as planned. I often revisit my notes in a desire for time travel, to plot a moment in time where things could have changed. Meghan Johnston coined the term ‘slow curating’, which highlighted the benefit of meaningful’ interaction of the local context, noting slow curating ‘employs relational and collaborative processes’. The process of developing relationships, reflecting and choosing how to interpret them, slowing down and taking stock of the given context in order to make the next move is a way to make meaning from the present. In TWHB, we had conversations on the haunting effects of ghosts in the archive, and often thought about refracting different curatorial choices through the prism of ‘local Sudan’ and ‘diaspora Sudan’, as well as the tension between individual, social and public remembering about images from archives. We changed our minds about how we felt about things, in relation to the changing contexts, and had the freedom to do so. Things were more possible because they were less fixed, and as Independent Curators, we had more control of the given context in order to stay rooted in the present.

L: Curation, in essence, is a process of manufacturing narrative, whether these narratives are a thread or the entire fabric of the archival material is determined by intentions of the curator. While handing the archive we are given the opportunity to pause and rethink our definitions of history and our relationships to it. Exhibitions as a site of manufacture provide us with the ability to reimagine the use of different archival materials to come up with new stories and new ways to tell them. If we treat them with enough care, archives resulting from curatorial activity can be spaces where we interrogate and challenge the fact and falsity of history. They can teach us about the power of narration in shifting focus, or completely diverting the truths of history. What curators learn most intimately when working independently with the archive is the utter fragility of history within the balance of truth and context. Curatorial activity can inhabit the many perspectives of the archive and the real challenge becomes choosing what takes up the most space within the stories being told. The amplification of unsung archives and anarchives is often framed as decolonisation, the venues, sites and spaces of exhibition can constitute reclamation, and all of these are curatorial choices and statements made from materials, which at their genesis, served the polar opposite purpose.

WHAT DO CURATORIAL ARCHIVES NEED TO BE SUCCESSFULLY UNFOLDED? IS ASKING THEM QUESTIONS ENOUGH? OR EVEN DIGGING IN THEM FOR RESEARCH, DISPLAYING THEM IN EXHIBITIONS?

H: There needs to be a clear purpose to starting curatorial archives in relation to how it can be beneficial. I ask myself, why do I keep and organise certain things from past projects? Usually they are mementos. They are quick snaps, not suitable for publication, or written notes of things I did not want to forget. Would anyone else be able to decode them if they were found, without my input? Increasingly, I do not usually have the time to keep and organise things systematically as I go along, like a physical research journal or similar. Particularly when I am working on multiple projects at once. For some projects, I may not own curatorial research I have created, and intellectual property may actually sit with a cultural institution. So then does the desire to keep an archive in those cases again come back to ownership and power? Needing to order writing, photos, and assume a sense of control as a curator? There has to be more than just collection and documentation, for its own sake. Perhaps the meaning I make from my own curatorial archive is limited, and I feel very differently about notes I initially made the more time goes on. I have become more comfortable with sharing snaps or notes from research on Instagram stories, in a more ephemeral context, and interacting with others. It disappears after 24 hours.

L: Like any research material, for curatorial archives to serve a clear and intentional purpose, they must be questioned. Asking questions about what inspired their creation or collection, what form they could take, and whether or not they even need a final form are all ways to uncover the possibilities of the archive. Often these archives are not elaborate and in essence are a simple catalogue of past projects. For a platform like Locale, this catalogue helps us trace down a lineage of production, it helps us place ourselves and the work that we do within a larger Sudanese context and track how we respond to the changing Sudanese reality.

WHAT’S THE FUTURE OF CURATORIAL ARCHIVES IN YOUR OPINION? WHAT ARE WE NEGLECTING?

H: In the exhibition TWHB, we questioned and problematised archives, as being repositories of knowledge and the limitations of physical archives being inaccessible. What these cultural practices mean in different contexts and voices from and to the Sudanese people, and how they are in production. We questioned our own curatorial work within the text: is this gathering and re-ordering of memories about nostalgia, or can it relate to the future? Do we depend on these experiences to produce knowledge about who we are, who we have been or who we could be—who are we without them? In this sense, I felt our curatorial activity was very public-facing in the themes ‘Searching for the Archive’, ‘Reclaiming the Archive’ and ‘Activating the Archive’. We needed the audience to engage with the exhibition to activate the archive, by helping us to explore these questions. However, even after the exhibition closed, many people who could not attend, interacted with us online, via email or DM, and this produced another kind of interpretation of the exhibition content online which became another archive, a palimpsest. I really feel like now [during/after the pandemic] there is a real purpose in moving things online and developing digital platforms on equal standing to the physical, not just as lip service to ‘going digital’.

L: For a while, a significant portion of the accessible Sudanese archive lived on internet discussion forums, this later moved to different niche blog sites and finally Instagram pages. Our previous projects and publications attempted to compile this information and produce artifacts that could be used as resources for certain subjects. Our digital publication, A Brief Introduction to Haqeeba, looked at genres of Sudanese music and their history and evolution by collecting material from these forums and through interviews with artists like Sammany Hajo, who is currently involved in the reinterpretation of classical Sudanese music, we were able to create a digital and therefore much more accessible publication. We’re currently witnessing the widespread acknowledgement of these online pages and the archive’s integration with different mediums and contexts due to the process of digitization and accessible archival materials being released on the Internet. In the wake of the revolution, people knew that they had participated in a significant historical event which created a deeper interest in documentation. This documentation took various forms both visual in terms of photography and footage and others more data-oriented in excel sheets and annotated maps of movement. TWHB highlighted some of the alternative archives that came about during this time such as ‘Archive of February 22nd ’ by digital artist Abdulrahman Al Nazeer which was a performative on-going archive in the form of an Instagram story. These acts of grassroots archiving created new spaces for discussion. In a way, the archive became less impenetrable, as people were able to highlight, add or refute certain narratives. This new form of participatory accessibility has created new possibilities to what the future of preservation could look like and how the process of present documentation will shape the archives of the future in terms of size, formats and themes as well as who authors them.

I’M CURIOUS TO KNOW MORE ABOUT YOUR OWN ARCHIVES… I MEAN YOUR PERSONAL ARCHIVE, HADEEL; AND THE ARCHIVES OF LOCALE, WHICH I IMAGINE OF DIFFERENT NATURE DUE TO THE DIFFERENT NATURE OF THEIR CREATORS…

H: I am inspired by Emily Pringle’s paper on ‘The Artist As Educator’ and approaching research interests like an artist, instead of an art historian who brings their canon of accumulated knowledge to a given context. There is an aspect of interrogating what you encounter through deconstruction, to make multiple meanings from it. I remember in 2016, as part of Sharjah Art Foundation’s Do It in Arabic that I curated in Bahrain for Al Riwaq Art Space, I made installations based on Ala Younis’ entry, ‘This Land First Speaks to You in Signs’, for visitors to carry on and add their own items to. It exposed the artistic process of creating links between seemingly disparate items, as having multiple interpretations. It was interesting to see the installation expanded over time as others intervened. The theme reflected the production of cultural identity in a personal way, as an aestheticised process, what we choose to show and what we leave out. When I was less busy, I hoarded stationary and would fill up drawers of notebooks with ideas for exhibitions and compulsively use post-its to jot things down. I even have multiple photos of post-its in different permutations when I am thinking out exhibition structures. It always wasn’t beautifully presented. I recorded shopping lists and to-do lists next to my curatorial ideas, but there was still a dissonance between what I had been doing that week and what I chose to record. I occasionally go back through them and I am struck by this. Now I almost exclusively use Instagram stories or posts as a form of archiving my ideas. I have a few instagrams actually, which I almost exclusively use as visual journals for different interests. I try not to get lost in aesthetics of how it is presented too much, although I am very visually-oriented so it can be hard not to get distracted by the presentation. I have had interesting conversations with peers about the term ‘the curator-artist’ another multi-hyphenated title that maybe describes something that we were already doing, in how we approach research.

L: The Locale archive is an accumulation of all our process work that formulates our final projects. Individually, the members of Locale come from different artistic backgrounds and disciplines which offers us a variety of literary and visual archives to pull from. Our experiences within the Sudanese identity are different but our relationship to home and belonging is often centered around the search for one. Our archive initially began as the consequence of this search but continued to grow as a purposeful research tool that helps us articulate this search into cultural productions. As an arts platform that works through collaboration with Sudanese artists, our archive is the clichéd Tennyson quote “I am a part of all that I have met”. When it comes to curatorial projects there is sometimes also the limitation of working within the framework of the available items. You are confined with curatorial projects, to a specific direction, a specific medium and you are bound by a specific truth. Artistic projects have more freedom to navigate different forms of story-telling. The introduction of fiction, imagination and interpretation makes artistic projects more malleable and expansive. With our exhibition, TWHB, happening right at the back of the Sudanese revolution, a time in Sudan when we felt like the entire country was watching an archive of their reality being built and manufactured in real-time, we thought it was necessary to interrogate this contention between art and archive. We introduced the theme of “Activating the Archive” which focused on documentations of the Sudanese revolution and the creation of a future archive that captured, beyond the facts of the revolution, the sentiments and the collective consciousness of the Sudanese people at that time. This was done with the intention of grounding the archive in the present and future, it was not a time for nostalgia but rather it was a time to look forward. We also felt this could not be done with documentation of the scene of the revolution alone, but required artistic interpretations of the struggle, strife and hopefulness of the Sudanese revolution. The interpretations, or artworks, were born of the archive but they allowed room for its manipulation. They reworked and questioned what it is that even constitutes an archive, and what qualifies to become a part of the archive.

HOW DO YOU USE THE ARCHIVE AND WHAT FOR?

H: Before curating TWHB with Locale, I was already interested in cataloguing Sudanese songs and other rituals performed by women, such as the zar and the bridal dances. I often looked at Twitter and Youtube for recordings and kept material to interpret and kept these on a folder in my laptop. The revolution was well under way while we were planning, and because I was not at the sit-ins I followed the creative outpouring taking place online, watching videos and Instagram stories and remixes of aghani banat that took place on social media platforms online. WhatsApp also became an important outlet for collecting news, sharing messages of hope and expressing fears. I had already started initiating oral history interviews about the zar and aghani banat in 2014, but I completed a series of new ones for an exhibition project which interacted with the themes of the revolution. There is a high volume of content to mine through, but it was useful for me to discuss with my relatives and then encountering many different perspectives. Most of this content doesn’t make it to exhibition due to licensing/copyright issues.

L: Just like many of our Sudanese peers of this generation, we are very much in a stage of discovery. There are many narratives yet to be understood and uncovered which have been stifled by the previous dictatorship and the effects of colonialism. We try to reflect on these difficulties that we face when producing work. TWHB posed questions about where our archives exist and why we don’t have access to them. The exhibition brought forth opportunities to work with various institutions in the digitising and preserving of the current Sudanese archive and, more importantly, making it accessible to people both in Sudan and outside of it. We use the archive through our projects and interpretations to respond to the cultural and political climate in Sudan. Following the exhibition, TWHB, we have opted to use the information we’ve gathered, and connections we’ve made to collectors, archivists and researchers through our discussion panels to work on a supplementary publication. Bringing together essays from many practitioners within different fields to narrate their experience and points of contact with the Sudanese archive. Locale always attempts to be future-facing, we engage with the community through the archive to start a conversation on how it is a way to access the past but also as a lens through which we view the present and the future.

HADEEL, CAN YOU TALK ABOUT “RECLAIMING THE ARCHIVE?”

H: Women from perceived ‘third world cultures’ are often historically represented in western anthropological imagery as objects, backward and monolithic. The aim was that the voices as well as the faces of women represented in TWHB were actively empowered. Their voices are not absent or silent—the songs and sounds of hamasa, sirah, arda, manahat, al-hikkmat are symbolic texts, and they are performances we can locate as fragments of our living history. Items that I had collected in a folder on my laptop started to snowball from interviews in 2014, and grew as the exhibition planning went on and my research deepened. In TWHB, we worked with material in ‘Reclaiming the Archive’ from historical records about Sudan, found as far afield as the United Kingdom, France and the United States. Within Sudan, Historical records of cultural preservation in the state capital of Sudan appear to have been largely established by senior members of the British administration ruling Sudan, as early as 1902. Archival records built in the early twentieth century, list well-known figures such as Lord Cromer, J. W. Crowfoot, Sir Reginald who contributed to establishing and developing the conservation of noted archaeological sites, as well as setting the foundation of collections and the museums which would display them. Documents such as ‘Sudan Notes and Records’ meticulously attempts to account for local phenomena, and their annotations have presented with an air of authority, without rooting its findings in any local cultural basis. Positionality is essential, and the same colonial gaze which ordered the ‘high’ arts and the ‘low’ folk arts into museum collections in a hierarchy of value, objectifies the people by talking and looking down at Sudanese customs and practices. Part of ‘reclaiming’ the archive is to write back against the annotations of anthropologists and historians, who once constructed and simplified meanings ‘on the record’ and drove the recording of our pasts. I also shared oral history interview soundbites with voices such as researcher Azza Ahmed Abdelaziz and performer and ethnomusicologist Al Sarah of the Nubatones, who introduced local context and talked about alternate modernities, and the soundscape by artist Hiba Ismail based on the zar looked for resonance through sound.

LOCALE, COULD YOU NAME ARCHIVE-RELATED PROJECTS THAT YOU WORKED ON?

L: As a collective, we collaborate with various artists, writers and creators to produce work that aims to revisit topics related to our political and social contexts. We try to approach materials and stories as perspectives and not as fact. We use these projects as a way to sift through the archive in its various forms and curate accessible and informative bodies of work. For us, this is the process of rebuilding the Sudanese archive. By retelling our inherited memory, we can examine and understand our past more honestly, better preparing us for what comes next. We believe that the archive presents itself in many forms in all disciplines. In the past we have focused on examining archival music in ‘A Brief Introduction of Haqeeba’, we have also looked at documenting our lived spaces in ‘The Room is the City’. Most recently we also worked with Khalid Al Baih and Larissa Furhmann to design and edit their recent publication ‘Sudan Retold’, which looks at retelling moments in Sudanese history through artistic explorations that blur the lines between fact and fiction, opening up new pathways for interpretation. There are many initiatives in Sudan with or through the archive and while some focus on the rigorous work of collecting and digitizing, many, like ‘The Urban Episode’ work in different ways that constitute the creation of alternative and counter-archives that examines changes in urban landscape through time. As a colonised people, our histories have always been written for us, we think that this is now a chance to reexamine them and write our present narratives through our own voices. We try to assert the role of Sudanese authors in the creation of work and research that responds to an on-going archive.

WHEN IT COMES TO ARCHIVES, WHAT SHOULD BE PRIORITIZED?

H: I would say using digital networks to activate them, beyond academic discussion or collection for posterity. I have tried taking part in initiatives with peers online—reading groups, collectives, Instagram groups. It comes from the desire to create processes that document the conversations and build them up as we go along, without attributing value. These projects try to work with flat hierarchies—the distinction between whether we are curators, artists, urbanists or journalists who are taking part and someone directing these discussions matters less, it is about how we approach collaborating together through our different perspectives. I am interested in continuing work on digitised sound material such as audio explorations and performances that are made accessible, in order for audiences to be creators as well as consumers. I am trying to continue pursuing audio explorations at the moment and trying to activate digital platforms which will allow for people to participate more readily.

L: Our current goal is accessibility. It is really important that we are able to not only view but also examine and challenge the archives. With that work comes the preservation of personal archives in their many formats. We view the archive as an instrument for research, there are many possibilities to draw comparisons and build theses from patterns in our histories. For us, the archive must be willing to open itself up to interpretation and form and hence curation. We hope that opening up these spaces for discussion and exploration by both individuals and collectives will allow for the rediscovery of our identities. By focusing on inclusivity and these untold stories we can counteract past erasures, allowing Sudanese people to see themselves in the archive.