YUKO HASEGAWA

THE ARCHIVE AS A CONCEPTUAL DRAWING

Kyoto, originally made in 2020,

reviewed in 2025

This interview has been conducted when Yuko Hasegawa was the Director of 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art.

Yuko Hasegawa is a curator, Research Professor at Graduate School of Management of Kyoto University, in “Curatorial Theory and Practice”; Program Director of Art & Design at the International House of Japan; Honorary Professor at Tokyo University of the Arts; and Former Director of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. She has been honored with the Commissioner for Cultural Affairs Award (2020), the Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France, 2015), the Order of Cultural Merit (Brazil, 2017), and the Officier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France, 2024). Hasegawa has curated numerous biennales: Istanbul (2001), Shanghai (2002), São Paulo (2010), Sharjah (2013), Moscow (2017), Thailand (2021); and international exhibitions including Japanorama: A New Vision on Art Since 1970 at the Centre Pompidou-Metz (2017), and Fukami: A Plunge into Japanese Aesthetics in Paris (2018). Her publications include Art and New Ecology: Anthropocene as Dithering Time (Ibun-sha, 2022); Japanorama: Un Archipel en Perpétuel Changement (Centre Pompidou-Metz Éditions, 2017); and Performativity in the Work of Female Japanese Artists in the 1950s–1960s and the 1990s (Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, 2010).

YUKO, COULD YOU ELABORATE ON THE PLACE OF ARCHIVES AND ARCHIVING IN JAPAN, IN PARTICULAR, ESPECIALLY IN RELATION TO THE QUESTION OR ORDER AND DISORDER? LET’S START FROM YOUR OWN ARCHIVE OR YOUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARCHIVES IN YOUR PRACTICE AS A CURATOR.

In my practice, archives are not static repositories but dynamic, interactive ecosystems. They are sites where order and chaos cohabitate—where ephemeral fragments, unexpected documents, and seemingly marginal traces form constellations of meaning. In Japan, archiving has often leaned toward order—systematised, hierarchical, fixed. But contemporary curatorial work demands that we embrace a more elastic, open-ended approach. At the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, we continue to experiment with how to collect, organise, and activate diverse materials—not just books, but ephemera like flyers, handwritten notes, and tickets. These materials often become valuable not by design, but by accident—encounters with knowledge that happen en passant. Regarding data, we have collected information on artists, as well as documentary videos of exhibitions and events held at the museum over the past decade. Photographic records from before the museum’s opening in 1999 have also been digitised. Additionally, the museum’s curators have established a process of conducting interviews with artists related to exhibitions and uploading them to the website during the exhibition.

HOW DO CURATORS ARCHIVE IN THE INSTITUTION YOU DIRECT?

Each curator manages their research materials—books, documents, and digital files—according to their project needs. Materials gathered during exhibition preparation are stored in shared folders, and physical resources are registered in a central reference room. However, there’s an important distinction: while infrastructure is shared, interpretive responsibility is individual. Derivative materials—notes, correspondence, fragments—are kept and organised according to each curator’s sensibility.

WHAT’S YOUR PERSONAL PROCESS OF ARCHIVING AND HOW DO YOU DISPLAY AND SHARE WHAT YOU PRODUCE WITHIN THE INSTITUTION?

When initiating a themed exhibition, I begin by assembling relevant texts and references. As the process unfolds, studio visits and field research generate incidental yet irreplaceable material—photographs, videos, sketches—which I consider “relational information.” Much of this is not collected intentionally, but becomes meaningful through context. I scan, list, annotate, and sometimes delegate parts of the digitisation process to our archive staff, especially for ephemera and materials I can’t process immediately. Original documents—particularly those predating digitisation, like faxes and handwritten notes—are kept in personal files, as their materiality carries affective and temporal weight.

EVERYTHING THAT YOU PRODUCED WITHIN THE MISSION OF THE DIRECTOR OF THE MUSEUM IS GIVEN TO THE ARCHIVE OF THE MUSEUM. RIGHT?

Yes, all institutional projects and their associated materials are archived within the museum’s system.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO YOUR OWN ARCHIVE? DO YOU CONSIDER, FOR EXAMPLE, TO DONATE IT ONE DAY TO AN INSTITUTION? HOW DO YOU USE THAT? DO YOU GO BACK TO IT FREQUENTLY? IS IT PART OF YOUR PRACTICE? IS YOUR USE OF THE ARCHIVE THIS DYNAMIC?

My personal archive is ongoing and intentionally incomplete. I have curated many exhibitions outside the museum context, and I hope to develop a digital version—a private library open to researchers. I am considering donating it to a university, but first I need to organise its components: books, ephemera, and digital data. At present, I use a modest system: thematic envelopes labelled with dates and contents. It’s not yet professionally structured, but it is an honest reflection of curatorial labour—layered, partial, responsive. Like many curators, I accumulate drawings, letters, photographs, and emails from artists. I’ve collected, things I’ve received from artists, and specific drawings. When engaging in dialogue with artists, they often begin by sketching drawings as proposals for their works. These are not studies but rather part of the artist’s creative process. When unsure about classification, we keep everything, including correspondence with artists and experts. When categorisation fails, I prefer to keep everything. That undecidability is itself a form of knowledge.

DO YOU ARCHIVE EMAILS?

Yes—selectively. I print and preserve key emails, especially those that capture conceptual negotiations or significant dialogues with artists. Over the past two decades, I’ve digitised some of these correspondences, but not systematically. There are better technical methods for email archiving, but for me, printing and filing retains a sense of encounter and context. These exchanges are not peripheral—they are the conditions under which the artwork emerges.

I THINK THAT ALL THE CURATORS THAT I HAVE MET HAVE THE SAME ISSUE, BUT THEY DEAL WITH IT DIFFERENTLY AND THIS IS ALSO A WAY TO UNDERSTAND THEIR PRACTICE.

WHAT DO YOU THINK IS NEEDED IN YOUR ARCHIVE? DO YOU IMAGINE, FOR INSTANCE, TO HAVE SOMEBODY TAKING CARE OF YOUR ARCHIVE? WOULD YOU LIKE THIS PERSON TO BE A PROFESSIONAL ARCHIVIST OR MAYBE A PERSON WHO ALSO HAS A CURATORIAL SENSIBILITY – THAT KIND OF CURATORIAL SENSIBILITY THAT ALLOWED YOU TO PRODUCE THE DOCUMENT?

Ideally both. A hybrid figure—someone fluent in archival science and curatorial thinking. Managing an archive is not just about preservation, but interpretation. My hope is to find someone who can navigate between structure and intuition—someone who understands that curating is not about mastering chaos, but metabolising it.

I THINK WE WILL REACH THAT POINT ONE DAY, BECAUSE THIS QUESTION IS BECOMING MORE IMPORTANT AS WE PRODUCE MORE AND MORE INFO, A BIGGER AMOUNT OF DATA EVERYDAY. WE ALSO HAVE THE ILLUSION THAT EVERYTHING WILL BE STORED, BUT IT IS MORE LIKELY THAT EVERYTHING WILL BE LOST IN THE END.

Chris Burden never used digital tools—he relied entirely on fax, which he trusted more than digital data. That scepticism made me more attentive to the fragility of digital archives. Similarly, Dump Type—a performance collective—has kept every proposal, sketch, and exchange across 35 years of collaborative work. Each person writes their proposals on paper, and discussions begin from the start. If there are 10 sheets of paper with individual proposals, there are 10 proposals. After that, they discuss and gather information to create a single archive. They don’t throw anything away. They keep everything. The archive they have is truly amazing, and they recently published a monumental1,100-page book. Can you imagine that? It’s truly wonderful. It’s exactly what an archive should be. They even held an exhibition that they curated themselves, without a curator. Their archive is not just documentation; it’s a polyphonic memory of co-creation. This is what I believe an archive can be: a living, collective organism.

IS THERE ANY PART OF YOUR ARCHIVE THAT YOU PREFER OR THAT YOU WORKED MORE CLOSELY WITH?

Yes—especially during the making of a biennale or thematic research phases. I read books and gather information in line with the curatorial concept. For instance, when I had a new idea of ecology, especially a post-human ecosystem. I collected lots of reference and materials from interdisciplinary genres. Also I’ve built up an archive on Japanese art and society in the 1970s, as well as on the interrelation between art and architecture in the 1990s. These materials are conceptual anchors that I return to, not out of nostalgia, but as a mode of non-linear continuity. I never replicate past research, but I revisit it to generate new vectors of thought.

WHAT IS YOUR DEFINITION OF AN ARCHIVE?

An archive is an interactive resource—a site of reactivation, not storage. It lives in the hands of those who access it.

WHAT IS ACCORDING TO YOU THE MAIN DIFFERENCE BETWEEN AN ARCHIVE AND A COLLECTION WITHIN A MUSEUM?

Collections are institutionalised and defined by value systems—what counts as art, what is collectable. Archives, by contrast, are more intimate and processual. They include sketches, correspondence, and documentary traces—the “infra-artistic” elements that form the ecology of production. These are often categorised as secondary sources, but they are primary in the logic of curating.

AS A TEACHER OF CURATORIAL AND ART THEORY, WHY DO YOU THINK CURATORIAL ARCHIVES COULD BE IMPORTANT FOR STUDENTS OF THE FUTURE TO UNDERSTAND WHAT WE ARE DOING TODAY AS CURATORS AND HISTORY OF EXHIBITIONS? HOW DO YOU THINK CURATORIAL ARCHIVES WOULD BE USABLE WITHIN THE FRAME OF WHAT YOU’RE TEACHING, FOR INSTANCE?

I integrate my own archive into curatorial workshops so students can trace the evolution of an exhibition—how a concept is formed, how it shifts through dialogue, how decisions are made and unmade. Sharing this process demystifies curating and foregrounds its epistemological complexity. If a student wants to study, for instance, Japanese female artists from the 1960s, I can make relevant parts of my archive available. The archive becomes a pedagogical tool—not just for understanding art history, but for understanding how curators think.

THE LAST QUESTION IS, WHAT DO YOU THINK IS THE BEST WAY TO ACTUALLY SHARE YOUR ARCHIVE AS A CURATOR? PERSONALLY, I THINK WE COULD FIND WAYS TO MAKE ARCHIVES MORE INTEGRATED TO THE VISUAL ASPECT OF THE EXHIBITION AS A THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION TO ITS DISCOURSE. SO THE EXHIBITION COULD BE A WAY TO DEVELOP OUR THOUGHTS IN THAT WAT, ESPECIALLY THROUGH NEW TECHNOLOGY. OF COURSE THERE ARE SO MANY OTHER WAYS, PUBLICATION IS ANOTHER ONE, CONFERENCES, TALKS AND MY FAVORITE ONES: THE ONES WE STILL DID NOT IMAGINE.

I WOULD LIKE TO KNOW THAT KIND OF PRESENTATIONS OF CURATORIAL ARCHIVES YOU HAVE THOUGHT ABOUT.

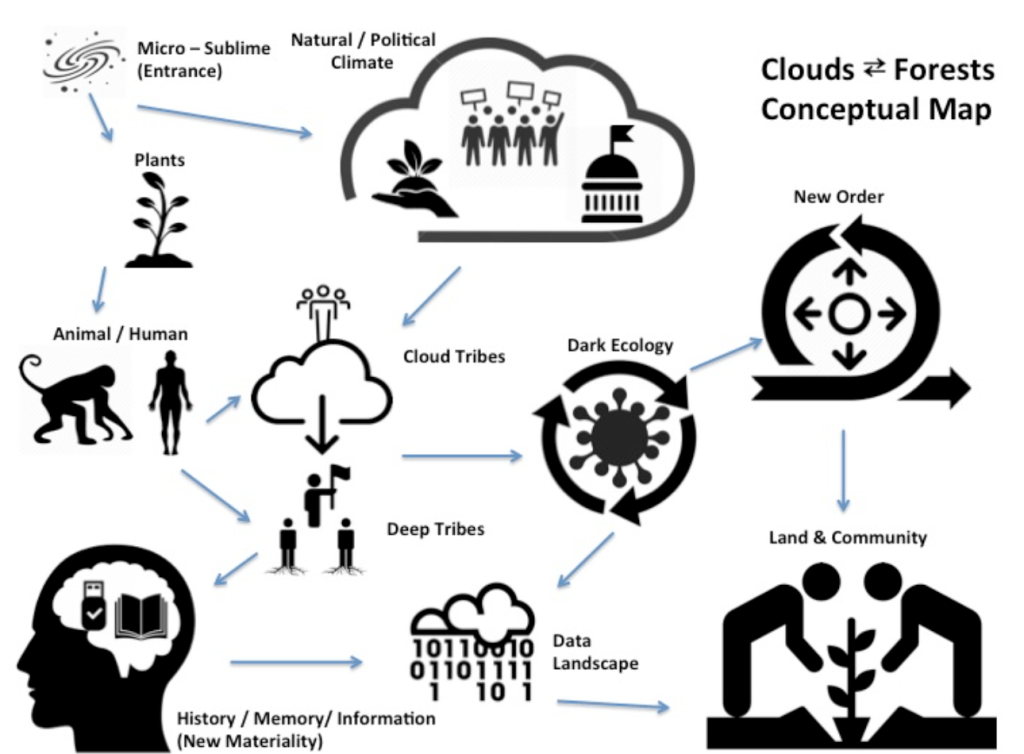

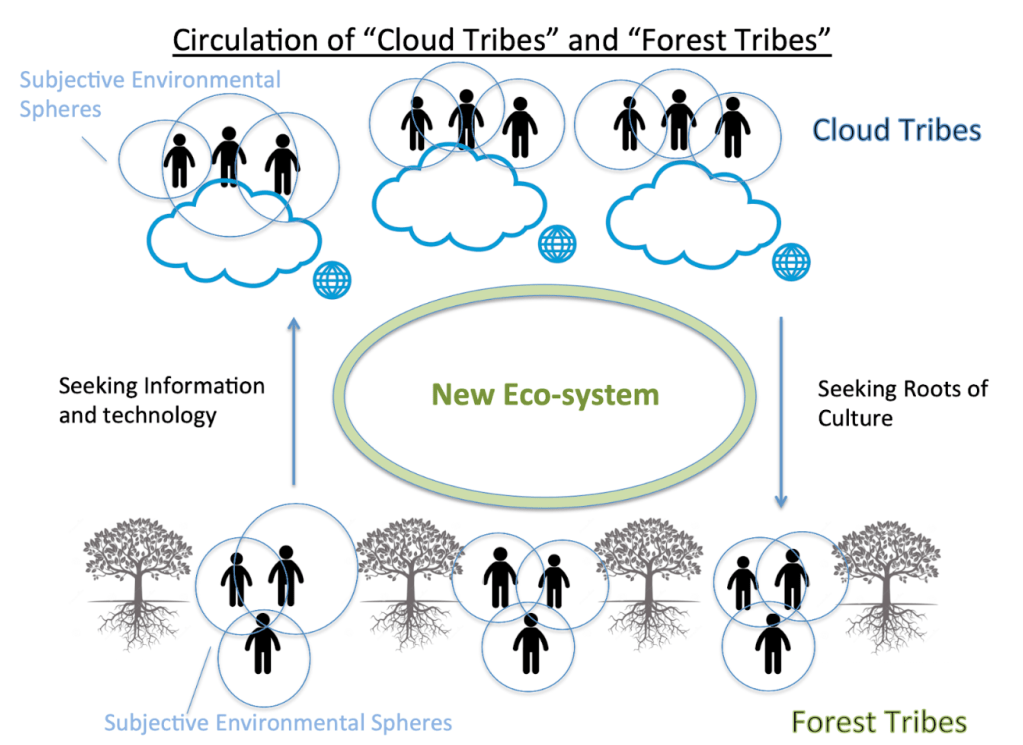

I am interested in transforming archives into a form of visual thinking. That’s why I document exhibitions, direct video recordings, and sometimes include the curatorial process itself as part of the exhibition. These become “second exhibitions”—parallel to the catalogue, but alive. I also want to show my own drawings and diagrams, which I use to communicate concepts with artists. These are not aesthetic embellishments; they are conceptual maps.

OH, I WOULD LOVE TO SEE ONE OF THOSE.

I want people to see my diagrams. I design them as ecosystems or constellations, incorporating playful pictograms. These visualisations are powerful tools for communicating exhibition concepts—especially with artists—because we operate in a field where visual language is our common tongue. During conversations around exhibition proposals, verbal explanations often fall short. These diagrams help clarify the invisible structure of ideas. We even displayed one of them at the entrance of the Moscow Biennale.

I WAS GOING TO ASK YOU IF YOU INTEGRATE YOUR OWN ARCHIVE ONTO THE DISPLAY OF YOUR EXHIBITION.

For me, sharing is essential. What initiates an exhibition? What is its internal logic, its architecture of thought? Diagrams allow me to map that generative process. Curating, as I see it, is fundamentally distinct from the work of art historians or critics, who often approach exhibitions as external analysts—observing and organising from a distance. In contrast, curators are embedded within the production process. We are participants in a reciprocal ecology of influence, shaped by temporal, cultural, and material contingencies. Within this context, I believe it is vital to treat the curator’s own archive not as supplementary, but as an active agent—a co-actor in the exhibition’s unfolding.

MANY CURATORS HESITATE TO INCORPORATE THEIR OWN ARCHIVES INTO THE EXHIBITIONS THEY CREATE. THIS IS BECAUSE THEY FEAR IT MIGHT BE SEEN AS “CURATORIAL INTRUSION”. I STRONGLY OPPOSE THIS LOGIC.

THERE IS NO HARM IN SHOWING WHAT THE EXHIBITION LOOKED LIKE WHEN IT WAS IN THE MAKING, AND THE MANY WAYS THE CURATOR CONTRIBUTED TO IT – IDEALLY. I AM HAPPY TO HEAR THAT WE AGREE, YUKO!