MASSIMILIANO GIONI

THE KNOWLEDGE-SEEKER ARCHIVE

New York, 2017

Massimiliano Gioni is the artistic director of the New Museum, New York, where he has curated solo exhibitions by Paweł Althamer, Tacita Dean, Urs Fischer, Goshka Macuga, Carol Rama, and Pipilotti Rist. Since 2003, Gioni has also been the director of the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi in Milan, curating shows and public art projects by, among others, Allora and Calzadilla, Paweł Althamer, Fischli and Weiss, Cyprien Gaillard, Sarah Lucas, Paola Pivi, and Tino Sehgal. Since 2021 he has taken on the additional role of Artistic Director of the Beatrice Trussardi Foundation. From 2000 to 2002, he was the US editor of Flash Art International. Along with Maurizio Cattelan and Ali Subotnick, he founded the Wrong Gallery in Chelsea, New York. Gioni was the co-director of Manifesta 5 (2004), and of the 4th Berlin Biennale (2006). He curated the 8th Gwangju Biennale (2010), and subsequently the 55th Venice Biennale (2013).

Courtesy Massimiliano Gioni

DO YOU HAVE AN ARCHIVE? IF SO, WHERE IS IT LOCATED, AND HOW DOES IT WORK? WHAT IS ITS STRUCTURE?

I am not sure I can really say I have an archive, as it is not fully organized and structured. I could say I have two separate tools that I often work with. One is a library, or more simply my collection of books, which at this point is divided between my apartments in New York and Milan, with some leftovers at my parents’ home, and in my office. There are probably around 10,000 books or so— I am not really sure: I have not counted them. The libraries are divided into group shows and monographs, with additional sections for theory and art history, general interest, and literature. I spend a lot of time and energy buying and looking for books. Typically, the books are bought or collected in New York. Then I decide which ones to keep with me and which ones to send to Milan. The ones that I think I need to access more regularly stay in New York, of course. Periodically I send off a dozen or so boxes to Milan. I pay someone in New York to pack the boxes and then I work with a person in Milan to unpack them and put the books in the proper order on the bookshelves.

Unfortunately, at this point I have run out of space both in New York and in Milan, and I need to find some kind of alternative solution, which I am not really actively pursuing. The problem is that I firmly believe books read themselves and read each other, so I am against putting them in storage, because by keeping them in active service, so to speak, moving them around the house, stacking them in piles as I think about a project or setting them aside for future research, I believe they actually influence and expand each other. I say this half-joking: I know it is not true, but somehow I absolutely believe it. I think that the more books mingle with other books, the more they contaminate each other with knowledge, and the less I have to read them all, as they can somehow telepathically pass on their knowledge to each other, and to me.

The whole library thing is quite depressing because I keep buying and amassing books and a fair amount of time and money goes into packing and shipping things around, but then again the library seems to me to be absolutely mediocre and irrelevant, or anyway much worse than the effort I put into it would suggest. Mainly I keep books and catalogs that I need for my research and so the library grows depending on which shows I am working on or which research I am focusing on at the time.

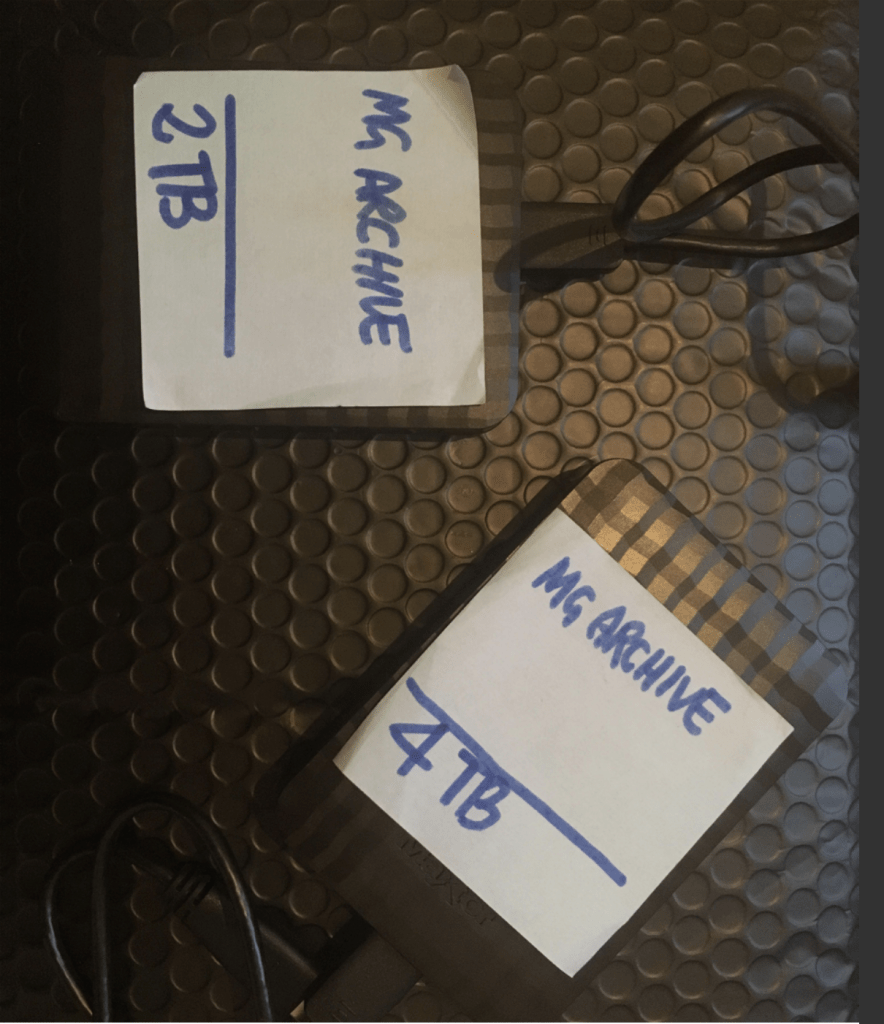

Then there is the proper archive which at this point is mainly digital, and which preserves some correspondence, primarily documentation of projects and exhibitions (with floor plans, checklists, budgets, etc.), ephemera, press, my own writing, and a few other things. A colleague and friend, Roberta Tenconi, works on the archive to organize and update it. I do not know exactly how many files it contains1 , but again I constantly remind myself that I forgot to file that email or copy that other document, so maybe I am just not systematic enough for these types of tools.

WHAT IS YOUR RELATIONSHIP TO THE ARCHIVE? HOW DO YOU USE IT, WHAT IS ITS ROLE IN YOUR PRACTICE AS A RESEARCHER AND CURATOR?

The books and the library are fundamental. For each show, I buy and collect as many books as I can get my hands on, and in the case of group shows, I can say that research using books and catalogs is as extensive as the research I do traveling or in studios. I remember reading somewhere that Flaubert amassed thousands of books as he was working on his novel Bouvard et Pécuchet, and for some reason that stayed with me. I guess it had to do also with the novel itself, which is such a parody of the quest for knowledge. And it is also useful to remember—with the help of Bouvard and Pécuchet—that most research is bound to be partial and fail…

As for the archive itself, I do not really use it much, unless I have to go back to look for something I have written and need to work on again or develop a bit further or republish. The other materials in the archive are mainly thought of as documentation of my own work, rather than as tools to make my own work.

DO YOU HAVE A DEFINITION OF THE TERM ARCHIVE, AND WHAT IS IT FOR?

I am not sure I have a definition of archive, beyond the common description of it as a collection of documents about a place, a person, or a topic. In fact, I must say that I have grown a little bored with the notion of the archive as it has crystallized more recently in the discourse around contemporary art. There have been hundreds of great and not so great exhibitions and books about the concept of the archive in the last ten to fifteen years, and the notion of the archive has become a bit of a cliché. So, in fact, some of my largest shows, like the 8th Gwangju Biennale and the 55th Venice Biennale, or The Keeper at the New Museum, were—in a sense—a personal attempt to avoid speaking about archives, even though the exhibitions included massive collections of objects and artworks. Perhaps I am more attracted to the idea of the collection— understood as a personal accumulation of objects, artworks, images, and documents organized according to individual criteria—than to the notion of the archive, which is inevitably connected with the idea of a superior authority. In other words, the archive is the order of the state, of the law, of history, and I tend to gravitate more towards the personal, flawed, and precarious order established by the individual, his/her private cosmology.

DO YOU HAVE A FAVORITE ARCHIVE?

Probably the Warburg Institute, for the way it has combined the personal, even tragic, adventures of its founder—Aby Warburg—and the openness and accessibility of a true great educational institution.

HAVE YOU EVER VISITED OR CONSULTED ANOTHER CURATOR’S ARCHIVE?

I was fortunate enough to work on a couple of occasions with Harald Szeemann’s archive, with Ingeborg Lüscher—Szeemann’s wife—first, and then with the Getty Research Institute (GRI) where the archive is now kept. With the help of Pietro Rigolo—who is a researcher working at the GRI on the Szeemann archive—I could explore some of Szeemann’s material related to his unrealized exhibition about motherhood, as I was researching my own show titled The Great Mother. It was a very inspiring process, which led to a contribution by Rigolo in The Great Mother catalog but, more importantly for me, gave me license to embark on my own project. As I was thinking about a show looking at the iconography of motherhood, I was of course aware of Szeemann’s unrealized project, but did not know much about it in detail and I was concerned I could not do my own show with this heavy legacy hanging above it. So the work on the archive actually liberated me and allowed me to do my own exhibition, because I soon discovered that Szeemann’s show was quite different from what I was envisioning, and, most interestingly, was not meant to contain any artwork or object that was typically recognized as such.

The first time I worked with Szeemann’s archive was when I was studying his show The Bachelor Machines as part of my research for an exhibition of my own about art and technology (titled Ghosts in the Machine, 2012). At that time, I contacted Ingeborg Lüscher and she was so kind to share many details and pieces of information about The Bachelor Machines. She allowed me to borrow the incredible reconstruction of Franz Kafka’s torture machine from the novel The Penal Colony, which Szeemann had commissioned for his exhibition in the 1970s. It is perhaps ironic that the object I borrowed from the Szeemann’s archive was inspired by Kafka, whose writings have often described the daunting intricacies of bureaucracy, and of archives.

I have also visited Germano Celant’s archive, which is quite impressive—already in 1970, at age thirty, Celant was curating a major show on conceptual art based on his own archive. That gives you an idea of its wealth.

And having directed the Venice Biennale in 2013, I had the honor of spending some time in the Biennale’s archive, which in a sense is the archive of archives, filled as it is with great correspondence, notes, and plans, from hundreds of curators, artists, politicians and much more. It should be a compulsory visit for anyone with an interest in art history. Like all archives, it is also a humbling experience, as it is a reminder that many came before you and many will follow, and that each name is nothing but a small speck of dust in history.

INDEED, I BELIEVE THERE IS A VISIBLE RELATION BETWEEN A CURATOR’S

WAY OF ARCHIVING AND HOW HE/SHE REALIZES A PROJECT. IF A CURATOR’S PRESENCE SOMEHOW STAYS IN THEIR DOCUMENTS AND OBJECTS, WOULD HIS/HER ARCHIVE BE A WAY TO UNDERSTAND THEIR PROJECTS BETTER? WHAT IS THE BEST WAY TO USE IT?

It might be my Catholic upbringing or some kind of romantic inclination, but I am afraid that, to me, archives always come with more than an intimation of mortality: in other words, they speak of the passing of time, of the vastness of history, of the ephemerality of each life. In that sense, they can also offer a sublime experience of vertigo as archives make us stand on the precipice of time. I know this sounds a little kitsch (and indeed there is always the risk of falling into sentimentality and kitsch when working with archives): there are plenty of questionable artworks inspired by archives, but, to me, archives have more to do with these feelings of mortality than with the aura or the energy of the person who created them.

WHAT IS THE INTEREST IN LOOKING AT A CURATOR’S ARCHIVE, IN YOUR OPINION? WHAT KIND OF AUDIENCE WOULD YOU LIKE IT TO BE ACCESSIBLE FOR?

I am not really sure if anyone will need or want to access my files in the future. Perhaps a student working on a thesis about an exhibition of mine, but that is already a presumptuous thought. Maybe that is why I am not even sure if my archive is any good or if it is useful: I have very few expectations about posterity or perhaps I am nervous and uncomfortable with the slightly narcissistic idea of personal archives. Or again I simply wish I were better at organizing one.

FOOTNOTE

- There are 348,579 files (April 2018). ↩︎