HOU HANRU

THE MEMORY-KEEPER ARCHIVE

Rome, 2017

Hou Hanru was the Artistic Director of of MAXXI, the National Museum of 21st Century Arts in Rome, from 2013 to 2023. He remains active as an independent curator, critic, and consultant, based between Rome, Paris and San Francisco. From 2006 to 2012, he worked at the San Francisco Art Institute as director of Exhibitions and Public Programs, and as chair of Exhibition and Museum Studies. He also co-directed the first World Biennial Forum (Gwangju, 2012). Hanru has curated and co- curated numerous exhibitions including China/ Avant-Garde (1989), Cities On The Move (1997– 2000), the 3rd Shanghai Biennale (2000), the 4th Gwangju Biennale (2002), the French and Chinese Pavilions at the Venice Biennale (1999 and 2007 respectively), the 2nd Guangzhou Triennial (2005), the 2nd Tirana Biennial (2005), the 10th Istanbul Biennial (2007), Global Multitude (Luxembourg, 2007), the 10th Lyon Biennale (2009), the 5th Auckland Triennial (2013), and Cities Grow in Difference, the 7th Shenzhen/Hong Kong Bi- City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture (UABB) (2017-18).

Photo: M3Studio, 2013

Courtesy Fondazione MAXXI, Rome

DO YOU HAVE AN ARCHIVE?

I have many archives, basically one for each of my projects. In the old days, it was easier to make an archive because there was more physical material such as slides, paper documents, faxes, letters, etc. Up to 2000, I have kept the documentation for every step of the projects’ evolution: the research, the technical and administrative parts, the press, photographic documentation, the project itself. After 2000, things became much more chaotic: everything is on my computer, there are many emails to go through and they can be lost easily. I can save about 80% of the material but, still, I am always surprised to see how digital facilities make life more complicated. There’s a bigger quantity of files but less time to put them in order anyway, so it is much more confusing. I don’t have an assistant who can look after these things and I archive everything myself whenever I can. I have a system, but it is far from being ordered and precise.

WHERE ARE YOUR PHYSICAL ARCHIVES KEPT?

At the moment they are in Paris, San Francisco, and in Rome, the places where I live and work. The Cities On the Move archives are currently in the Asian Art Archive in Hong Kong and are being digitized. There is also material in China, but very little.

INTERESTINGLY, YOU HAVE YOUR ARCHIVE ON YOUR LAPTOP, RATHER THAN AN EXTERNAL HARD DRIVE. IT IS AS THOUGH YOU ALWAYS NEED YOUR ARCHIVE TO BE WITH YOU WHEN YOU ARE WORKING IN YOUR OFFICE, TRAVELING OR AT HOME, EVERYWHERE AND AT EVERY MOMENT, READY TO BE USED.

Yes, I always work on and use my archives. I mostly produce presentations and papers from them, which happens very frequently, and is the reason I need to have everything available. However, I am not obsessed by this idea. I do not want them to be a monument to myself, and they are not meant to be comprehensive. I remember where things are, so I can go and pick up a document in San Francisco if I really need it. That said, I have an archival index that is quite practical. In this way, I have a list of every text, catalog, and exhibition that I have produced.

WHAT IS YOUR UNDERSTANDING OF WHAT AN ARCHIVE IS?

For me the archive is a tool I can always go back to. It is a memory-keeper. I do not consider my archive as a collection of objects. Of course, some really beautiful things may be kept in it, as is the case with art critic and curator Kim Levin. For many years, she collected all the invitation cards she received and then showed them alongside her notes and sketches written on the back of the cards at Kiasma, Helsinki, in 2009.

WOULD YOU BE COMFORTABLE SHOWING MATERIAL FROM YOUR ARCHIVE?

If others would like to use it then I would agree, but I would not personally show it. Archives are objects you can think about and look through. I find pleasure in digging into them, but I do this very rarely because I don’t have time for such activities. I have explored the idea of having a website with my own professional records, for me to understand them more clearly by giving them some sort of order, and to allow younger people to discover these archival sources. I have not managed to do it so far; it requires a lot of time.

YOU ARE NOT ALONE! I HAVE DISCOVERED THAT THE MAJORITY OF CURATORS PROCRASTINATE WHEN IT COMES TO TAKING CARE OF THEIR OWN ARCHIVES. BUT LET US TALK ABOUT THE WAY YOU DEAL WITH ARCHIVES AT THE INSTITUTION YOU ARE DIRECTING, THE MAXXI IN ROME.

This institution is very special because it was conceived not only as a museum but also as a research center. We document all the museum’s activities. We also have documentation of the construction phase of the building, a lot of images of the whole development of the institution. We have very well-organized archives and our team carefully documents every step of the exhibition-making process, especially through photographs and videos. Also, we publish an annual report, in which you can find the cultural program of the whole year with a description.

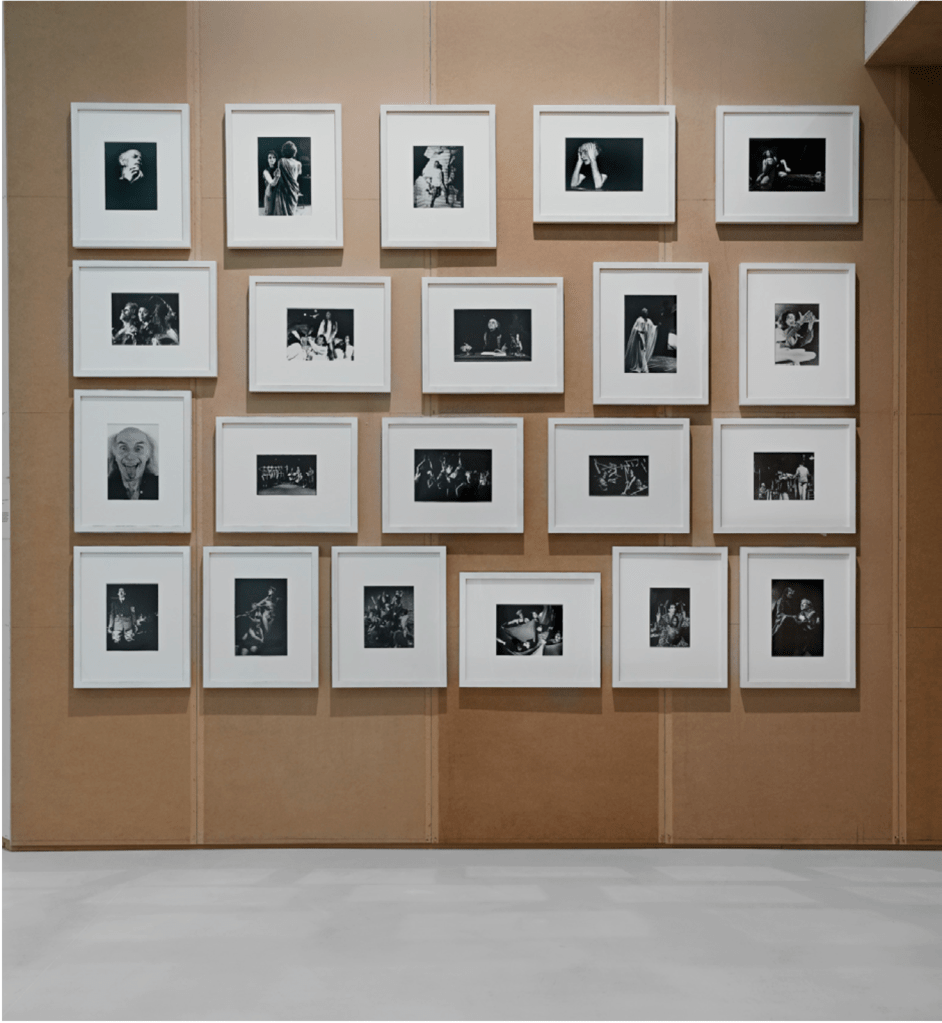

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE WAY OF EXHIBITING THE MUSEUM’S ARCHIVE?

It depends on the needs and purposes of the exhibition’s documentation that one wants to show. Archives have many forms and functions: sometimes they are for research; they are also objects that can be aesthetically appreciated, for example Carlo Scarpa’s archive we have here at MAXXI. There are hundreds of cigarettes boxes, where he noted down his ideas in drawings. I sho- wed them in my first exhibition here in 2014, the title was Non basta ricordare [Remembering is not enough]: more than 200 works by seventy artists and architects in dialogue with each other and with the space, emphasizing the profound vitality of the museum’s collection. The idea was to show that a collection, or an archive, is not just meant to be remembered but can be reactivated to create new meanings. This is the show in which the archive and the artworks were most integrated.

WHAT ARE THE MAIN SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE COLLECTION AND THE ARCHIVE?

The materiality of documents and artworks is probably what makes archives and collections similar. For some artists, research documents are part of the work itself; therefore, it is very difficult to find the dividing line. This says a lot about the way artists use categories—if we think about the artist Huang Yong Ping and the solo exhibition he had here at MAXXI in 2014-15: the role of the archive was not to simply be documentation of his research, but also to appear as art itself.

THE ARCHIVE IS NOT ABOUT ILLUSTRATING SOMETHING.

It is about proving the diversity of ways in which we can look at facts. It is a political question: building archives also means to construct the mind of the institution. There is an organic combination of different elements and layers that make up the institution that one can find reflected in the archive, and that escapes the definition of Truth with a capital T.

THE ARCHIVE HAS TO QUESTION THE INSTITUTION ITSELF.

Absolutely. There is a lot of evidence in the archive and politicians take advantage of this very often to impose their own visions. Archaeology is such an important discipline, because knowledge is based on history. Facts lie in the archives; that is why they are so important for the establishment. Manipulating facts leads to the manipulation of truth, and to power. As a museum director, I have the responsibility to always question the material we have in the archives and in the collections. If the institution wants to keep on being a place that makes sense, then it must maintain the freedom to question what exists at the very core of its ideology, to deconstruct by looking back to the past. A good institution is always a living one; it has to challenge its own structure and ideology.

THE NOTION OF THE ARCHIVE IS UNDERGOING AN IMPORTANT SEMIOTIC TRANSITION. WHAT FEATURES SHOULD WE KEEP AND IMPLEMENT FOR THE FUTURE?

That is an interesting question. Now there is a new “archive fever” encouraged by the establishment using the archive to justify certain professional behaviors and to avoid risks. When you own the archive, you basically own the authority to say: “what I do is to represent the Truth.” I accept that art historians can be interested in digging into archives but I am skeptical of colleagues who do so in an obsessive way, for they become technocrats bound to these materials. I hope that in the future people will understand the anxiety behind this attitude and overcome it.

I HAVE THE FEELING THAT THIS FEAR IS PART OF OUR TIME. MY GENERATION HAS A DESIRE TO PUT IN ORDER THE HUGE AMOUNT OF INFORMATION WE HAVE ACCUMULATED, ALONG WITH WHAT WE HAVE INHERITED FROM THE PAST, MAYBE HOPING TO MAKE SENSE OF IT.

Yes, you need security. This is part of a global tendency conceived by governments and the main economic system: control through a culture of fear. I hope that people will be able to fight this feeling. We are so obsessed by the idea that we should do the right thing that sometimes we forget the importance of being wrong.

I HOPE SO TOO.